Comics in Italy have a long history which dates back at least to 1908. That year the Corriere dei Piccoli (“Courier of the Little Ones”) started to make a regular feature of publishing comic strips. Over the following decades some series received critical acclaim and enjoyed enormous popularity, some catered for niche markets. Collana eroica (“Series of heroic stories”) featured an array of graphic novels intended to appeal to a male readership interested in wartime action, adventure and escapade. Originally published by Fleetway Publications London, the series was translated into Italian by Editorale Dardo, a Milan-based publisher that re-issued the comic strips for the Italian market in the early Sixties. Titles and subtitles, by necessity, were produced by Milanese editors. Cover arts are uncredited.

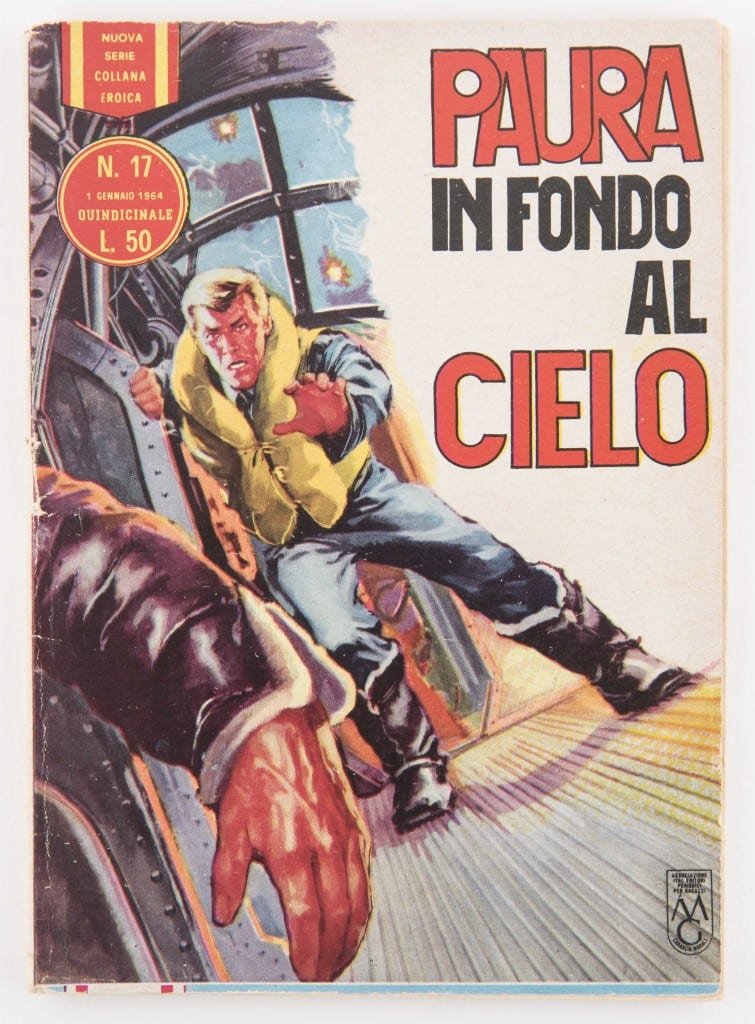

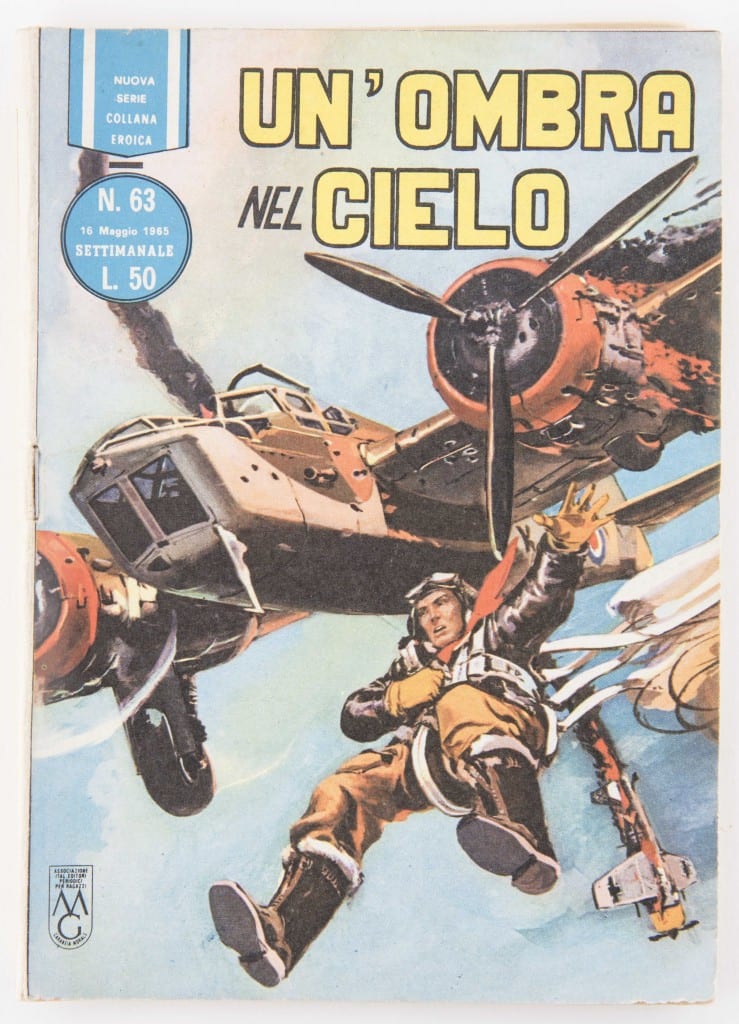

Some titles are straightforward such as Un’ombra nel cielo (“A shadow in the sky”) or Paura in fondo al cielo (“Fear [lurking] deep in the sky”). Others covers cast light to the unresolved ambiguity that marks the cultural reception of the bombing war in Italy. Allied air forces inflicted suffering and damage on an unprecedented scale, but were at the same time the liberators who helped defeat Axis powers.

The three bombers with invasion stripes featured on the cover are straightforward and unproblematic, but the wording reflects a rather intricate situation. To begin with, it is surprisingly difficult to translate into English the sentence Gli occhi della notte. Passano nella tempesta di fuoco come angeli votati allo sterminio, as it is based on a probably deliberate vagueness and double entendre. A possible English equivalent is something like: “The eyes of the night. They fly through the firestorm, like angles united by a covenant of annihilation”. However, the sentence can also mean: “The eyes of the night. They fly through the firestorm, like angels expecting to die”. The latter reverses the meaning also conveying a somber, pensive undertone. A reader conversant with aerial warfare could immediately associate the firestorm to the bombings of Hamburg and Dresden, but the Italian tempesta di fuoco could refer equally well to heavy artillery barrage, especially flak. There is also an even more unsettling innuendo, because the noun sterminio (lit. extermination, annihilation) is a widely used synonym for the Holocaust in spoken Italian. It’s fascinating to see how consumerism media intended for mass consumption may be overflowing with symbolisms, multi-layered allusions and ingenious word plays. It’s not unexpected that the mystique of flying – combined with a mythology of manhood – had an enduring appeal to an action-thirsty readership. What may come as a surprise is that this happened in a country which suffered heavily as a consequence of the bombing war, less than two decades after the end of the conflict.

These covers have been featured in the International Bomber Command Centre as digital interactives, a fitting example of the fascinating complexity of war heritage.

Alessandro Pesaro, Digital Archive Developer