In September 2017, Dan Ellin posted an account of the provenance and progress of the IBCC exhibition. In the light of the exhibition now being completed, we reflect further in a two-part post on our approach to interpretation, particularly the difficulties in dealing with difficult heritage.

Remembering the bombing war still generates strong and conflicting opinions and getting the tone right for exhibitions about Bomber Command is notoriously hard. Even trying to explain why this is the case tends to generate more heat than light.

When the University of Lincoln became involved in the memorial to RAF Bomber Command in 2013, we believed that a capacious and sensitive handling would go a long way towards promoting an innovative and inclusive approach to this contested issue. Three things should be noted here. Firstly, by this stage, many museums and heritage attractions dealing in war had come round to the view that their holdings represented ‘difficult heritage’ and were actively trying to engage discussion as to how to deal with this; perhaps the National Army Museum in London was the leading example in the UK.[1]

The International Bomber Command Centre

Secondly, we were aware of two Canadian controversies regarding the bombing war. In the early 1990s, a three-part TV documentary, The Valour and the Horror, was aired; the second part, ‘Death by Moonlight’ dealt with the bombing of Germany. This unleashed vigorous, not to say vitriolic, public debate, leading to Senate hearings.[2] Then in 2006, the Canadian War Museum was engulfed in controversy over the wording of a small amount of exhibition text on the bombing war. Veterans’ groups demanded it be rewritten. Once again this reached the Canadian parliament. The CWM were forced to do so, even though a panel set up to adjudicate the matter found the original wording to be historically accurate.[3]

Thirdly, we felt that there was an opportunity in Lincolnshire to rise above regional commemoration and to embrace a truly international perspective in our approach to the memory of Bomber Command. This meant not only acknowledging the remarkable internationalism of those who served in the RAF and were posted to the Command, but also the very far-reaching consequences of bombing both friend and foe in mainland Europe, and the many complexities that the bombing war continues to reveal. In this sense, we felt that the University was playing the sort of role that such an institution ought to play: opening up debate, leveraging resources, connecting to contemporary trends.

A further factor came into play that fitted well into our attempts to be inclusive. The land on which the IBCC has been built belongs to an Oxford college, whose head required, in return for a long-term lease, that we gave due consideration to the German perspective of the bombing war.

Taking all such factors into account, and following the advice to us by one of the leading museum directors in the UK to ‘have a brave story and stick to it’, we devised an interpretation plan. This plan, and the exhibition to which it has given rise, were discussed from inception to the final sign-off of content with all the people who were a part of this project – and many others besides.

The plan committed to a narrative voice that focused on the people’s bombing war (oral testimony and personal memorabilia are the basis of the archive on which the exhibition is based); presented an ‘orchestra of voices’ to include those caught up in the bombing war in the air, on the ground and on both sides of the conflict, as well as those affected by the legacy of the actions of Bomber Command; acknowledged that pain and suffering were shared; and raised questions about the complexity of the bombing war, rather than delivering judgement.[4]

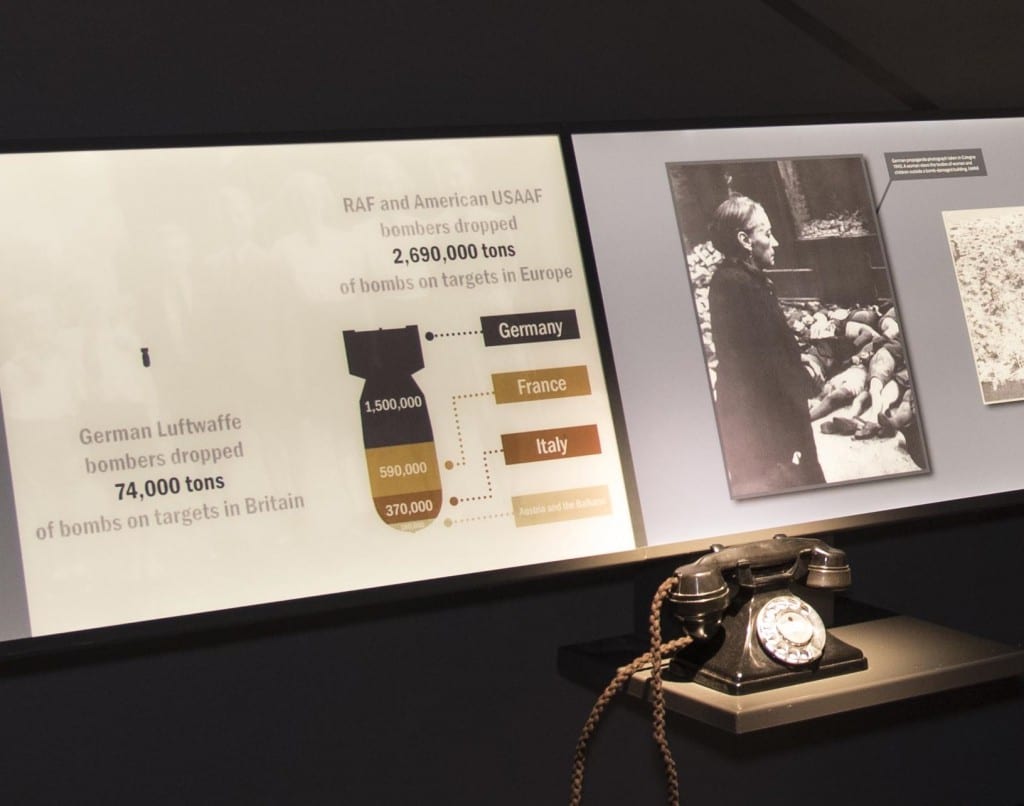

Telephone handsets are one way the orchestra of voices is delivered. (IBCC)

The IBCC embraces three values that also underpin that interpretation plan: recognition, remembrance and reconciliation (http://internationalbcc.co.uk/about-ibcc/). The first two values are not so difficult to define. Recognition relates to veterans, whose role has been downplayed because of ongoing discomfort in our society about the morality of bombing. Remembrance includes the hundreds of thousands who were killed, on both sides of the war. Reconciliation has always been the most challenging. It requires an acknowledgment that the suffering endured through a brutal conflict was shared and thus constitutes a basis for mutual understanding and empathy. It is also about acknowledging that not everything done by the winners of the war was just or right. Reconciliation is not about triumphalism, heroism and victimhood; it is about our common humanity. This in turn enables the possibility an open and frank dialogue about the bombing war, which remains a difficult and painful subject, capable of arousing strong emotion on all sides.

Dan Ellin, Heather Hughes and Alessandro Pesaro

[1] http://advisor.museumsandheritage.com/features/national-army-museum-reopens-following-three-year-23m-development/ accessed 15.01.2018.

[2] See Erwin Warkentin, ‘Death by Moonlight: a Canadian debate over guilt, grief and remembering the Hamburg raids’. In Wilfried Wilms and William Rasch (eds) Bombs Away! Representing the Air War over Europe and Japan. Amsterdam, Rodopi, 2006, pp. 249-264. Bercuson, D. J. and Wise, S. F. (eds.) The Valour and the Horror Revisited, McGill-Queens University Press, Montreal, 1994.

[3] There are several accounts of this incident; see for example David Dean, ‘Museums as conflict zones: the Canadian War Museum and Bomber Command’. Museum and Society Vol. 7, No. 1, 2009, pp.1-15.

Bercuson, D. “The Canadian War Museum and Bomber Command My Perspective” Canadian Military History, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2011, pp.55-62. Bothwell, R. Hansen, R. and Macmillan, M. ‘Controversy, commemoration, and capitulation: the Canadian War Museum and Bomber Command’ Queen’s Quarterly, Vol. 115, No. 3, 2008, pp.367-387.

[4] There were other factors to consider, as well, besides the content, including appropriate means of delivery. For a discussion of the issues, see for example Mad Djaugbjerg, ‘Paying with fire: struggling with ‘experience’ and ‘play’ in war tourism’, Museum and Society Vol. 9, No. 1, 2011, pp. 17-33.