Treviso, a medium-size town in the Veneto region and railway hub, was heavily hit by Allied bombings during the Second World War. The most intense one was the 7 April 1944 USAAF operation, in which over 2,000 people died and whole neighbourhoods were razed to the ground. Since the inhabitants were in the region of 60,000 (61.129 according the 1947 census) the impact on local society was devastating.

The memorialisation of the event has followed a complex trajectory. It was immediately appropriated by Fascist propaganda and held up as a prime example of Anglo-American viciousness; subsequently, it entered popular culture surrounded by layers of misinterpretations and wartime lore. A persistent legend has that the real target was either a meeting of Axis leaders who happened to gather at a local hotel, or that the city was bombed due to a phonetic and spelling similarity with Tarvisio, the latter being an important station on a vital railway line linking Austria with the Po river valley. In both cases the event was probably seen through the lenses of causality and sense-making – death and destruction cannot descend from the sky for no particular reason, there must be a clear-cut, wholly satisfactory explanation, even better if it frames the event as part of a bigger plan. The event was also at the centre of Giuseppe Berto’s novel ‘Il cielo e’ rosso’ (The Sky is Red). Published in 1947, it tells the story of abandoned young people in war-raged Treviso.

The bombing partially faded into oblivion during the following decades until a grass root movement brought it back to the forefront. This effort was led by Luisa Tosi, a local researcher under the aegis of the ISTRESCO (Istituto per la storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea della Marca trevigiana), an organisation within the nationwide Istituti della resistenza network. Luisa recorded fifty-odd audiocassettes accompanied by detailed annotations. This laudable effort can be understood by placing the Istituti della resistenza network in the broader context of post-war Italy. In the difficult years following the end of the conflict, they acted as trusted repositories for private papers, documents, photos and other memorabilia that found no place in local and national archives. This happened either because their creators wanted to maintain some forms of control on the way the material is accessed and used, or because of the sensitivity of the content: the Resistance, social struggles, political activism, campaigns for rights and the like. This collection is therefore part of a wider societal landscape.

Some snippets have been transcribed and published, but the bulk of civilian stories are still in their original tape format. There are many concerns regarding the rapid obsolescence of the cassettes, with the concrete possibility that these resources will soon be unusable. Preliminary contacts have been established as to digitise the tapes and – possibly – to publish the audio files under the auspices of the IBCC Digital Archive. While it was readily acknowledged that digitising the interviews is the most appropriate step toward long-term preservation, publishing them raised some issues. Their legal status is not entirely clear, as it frequently happens for most oral histories taped in the past; furthermore, the opportunity of sharing ownership of community memory with an organisation that has no obvious ties with Treviso was considered either an opportunity to place local history in a broader context or a risk of relinquishing control.

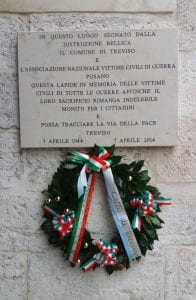

On the 6 April 2019, a representative of the University of Lincoln was invited to deliver a talk on the anniversary of the bombing. The event has a deep significance since the memory of the event is still a painful one. This is proved by a marble plaque on Palazzo dei Trecento, Treviso city council headquarters.

The plaque remembering the bombing, unveiled 70 years after the event.

Its wording throws in sharp relief the contradictions surrounding the bombing war in Italy: Allied forces were at the same time liberators and tormentors; they ended an oppressive regime but inflicted suffering on a massive scale in the process:

“On a spot marked by wartime destruction, the Treviso City Council and the National league of Civilian War Causalities laid this plaque in remembrance of the civilian victims of all wars. May their sacrifice be never forgotten, may this indicate the road to a future of peace.”

Not surprisingly the message is imbued with elusiveness: aerial warfare is merely hinted at, while ‘wartime destruction’ is not only ambiguous but omits completely agency. Who dropped the bombs remains unsaid. The plaque is also dedicated to the victims of all wars, and their death placed in a broader perspective of peace. It’s interesting to point out that ‘sacrificio’ has the same meaning and the identical moral connotation of ‘sacrifice’ in English, i.e. to willingly offer their own life in furtherance of a higher, nobler cause. Hardly the most accurate description of the death of non-combatants who merely happened to be at wrong place at the wrong time. Finally, the plaque was unveiled in 2014, 70 years after the event.

The presentation took place at the local library, the conference space packed to capacity at the start of the event.

Public attending the presentation.

The talk had to be carefully planned as not to obfuscate the controversial nature of the topic, while at the same time acknowledging the sensitivity of the context. The presentation was well received and the public especially appreciated a refreshing international perspective on a topic which in Italy tends to be explored from a narrower military history perspective. A member of the public commented: “I wish something comparable could be delivered here!”

Alessandro Casellato, the host, sounded out the public option as to whether the cassettes should be handed over for digitisation, a sort of impromptu exercise in community participatory practices. No objections were raised.

Alessandro Casellato (University of Venice ‘Ca’ Foscari’) hands over the cassettes to Alessandro Pesaro (right), representing the IBCC Digital Archive and the University of Lincoln.

Alessandro Casellato’s summation captures the mood of the event:

“The collective memory of the bombing of Treviso is still a painful one. Preserving the voices of those who were caught up in it is important for us – the kind offer of the University of Lincoln is an opportunity we’re grateful for. However, this hasn’t been an easy decision. Sharing the ownership of our past with an organisation based in a country which emerged victorious after the World War has made some of us uncomfortable; ethical problems have been debated at length; furthermore, there’s an obvious imbalance of power in terms of resources and expertise. As a preliminary step, we’re happy to entrust the cassettes to the University of Lincoln for digitisation and preservation, pending a future discussion on their publication”

In July 2020 all tapes have been converted into digital files and the cassettes returned to ISTRESCO. Discussion regarding the publishing of the interviews have been initiated.