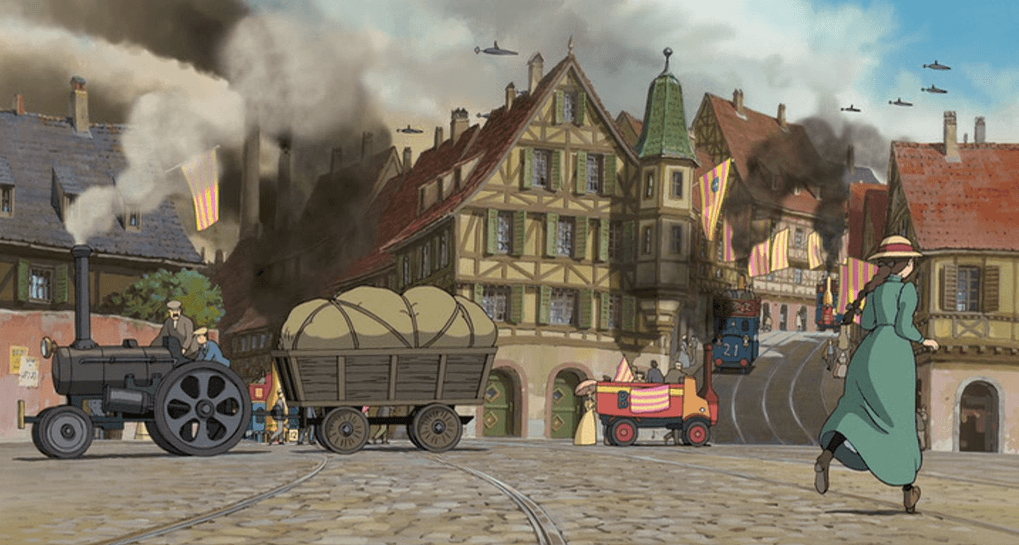

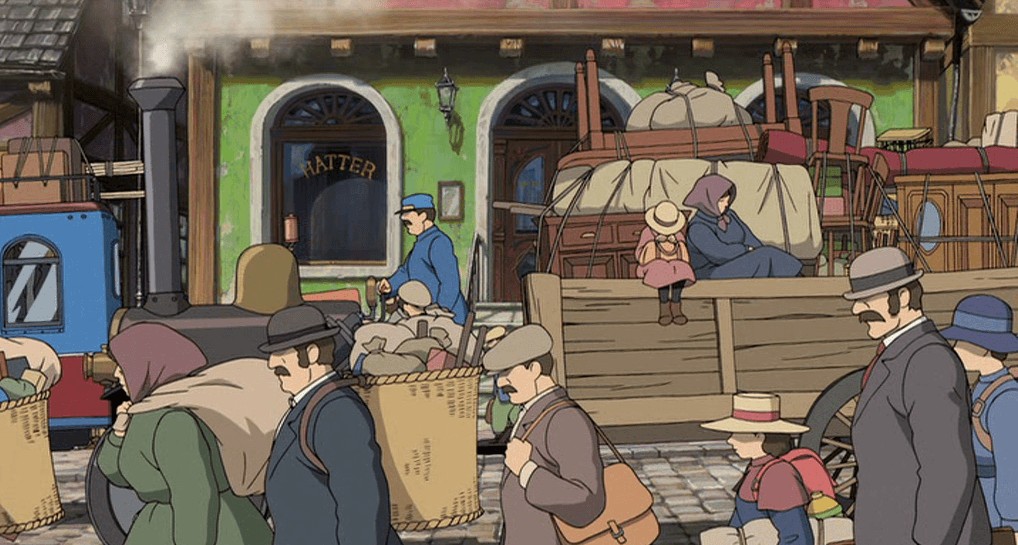

Howl’s Moving Castle (Hauru no Ugoku Shiro) is a 2004 Japanese animated film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. The plot is loosely based on the novel of the same name by Welsh author Diana Wynne Jones, originally published in 1986 by Greenwillow Books of New York. The movie is set in an alternative universe in which steam-based technology coexists with sorcery: wizards enjoy a socially recognised status and magic is used for dealing with issues ranging from delicate state matters to everyday problems. Neither time nor space are revealed but many elements seem compatible to early 2Oth century central or northern Europe.

Heavy steam haulage, parasols, petticoats, and half-timbered buildings define the fictional universe in which the movie is set. Only aircraft seems to be incongruous.

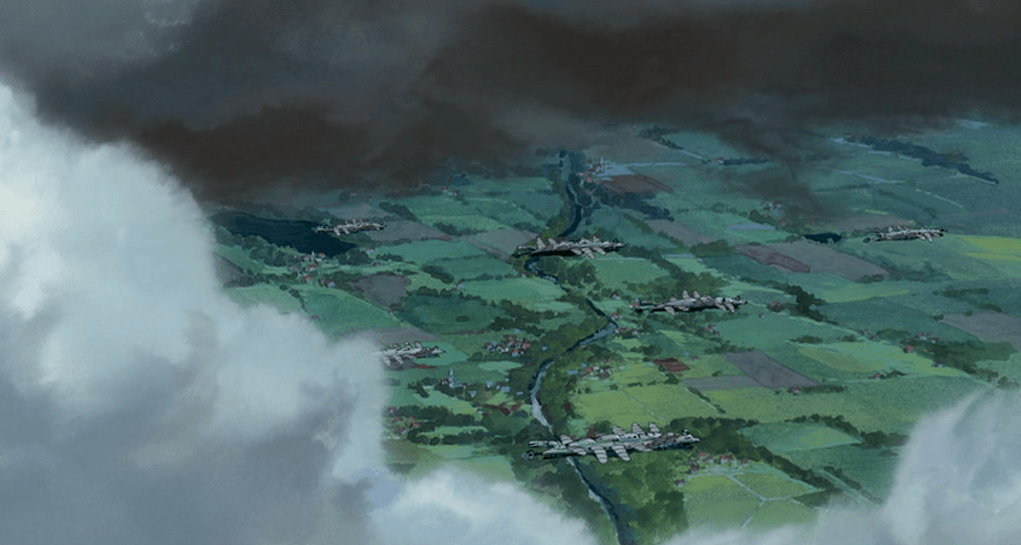

The heroine, Sophie, is a young unprepossessing hatter who is already resigned to a humdrum, uneventful existence. Her life changes abruptly when she meets the young and charming wizard Howl. The evil Witch of the Waste takes issues with their attachment and casts a spell on Sophie, who ages prematurely. The plot revolves around her attempts to lift the spell, defeat the jealous witch, and disentangle a second curse linking Howl, his castle and the fire spirit Calcifer who keeps the edifice moving. In the end, both spells are lifted: Sophie regains her real age, she and Howl can fulfill their love, and the castle is transformed into a flying machine carrying away the new couple. It is essentially a story of redemption through love and compassion combined with a strong critique of modernity, with an emphasis on responsible use of technology as well as a transparent anti-war message. A subplot follows the all-out war between two neighbouring kingdoms. Belligerents’ claims are unclear but fierce battles are fought on land, at sea and in the air. Civilian life is initially unaffected until war escalates and it is no longer confined to the battlefields – enemy aircraft start to attack cities. The air-raid siren is heard for the first time by nervous characters while evacuation of civilians commences.

An avowed pacifist, Miyazaki did not conceal his condemnation of the US-led War on Terror in the post-9/11 political context, especially regarding the second Gulf war (2003). The movie was a deliberate attempt to show his contempt for the intrinsic folly of war and his deprecation of the United States’ pugnacious policy. He openly stated that “the film was profoundly affected by the war in Iraq” (Gordon, 2005, p. 62) at a time in which there was a widespread fear that Japan could be dragged into an oversea war as an ally of the United States. His position is echoed by producer Toshio Suzuki “When we were making it, there was the Iraq War […] From young to old, people were not very happy” (Cavallaro, 2006, p. 170).

Not surprisingly, Howl’s Moving Castle has mainly been interpreted as a condemnation of war per se, without references to actual conflicts. Combat scenes are usually described as symbols, visual metaphors of violence rather than precise allusions to historical facts the viewer is supposed to decode correctly. At least one film critic mentioned the references to bombing warfare in the Second World War (Smith 2011), but this has been mainly overlooked in favour of a more symbolic interpretation, an example of the latter being (Arnaldi 2017). Not surprisingly, Howl’s Moving Castle doesn’t figure in the canon of works inspired by or at least influenced by Bomber Command.

It can be argued that Howl’s Moving Castle contains not only allusions to the bombing war waged by Allied air forces in Europe during the Second World War, but also surprisingly precise references to actual Bomber Command practices. The reason this point has been largely overlooked is unclear but has probably something to do with the preponderance of supernatural and symbolic elements in the movie.

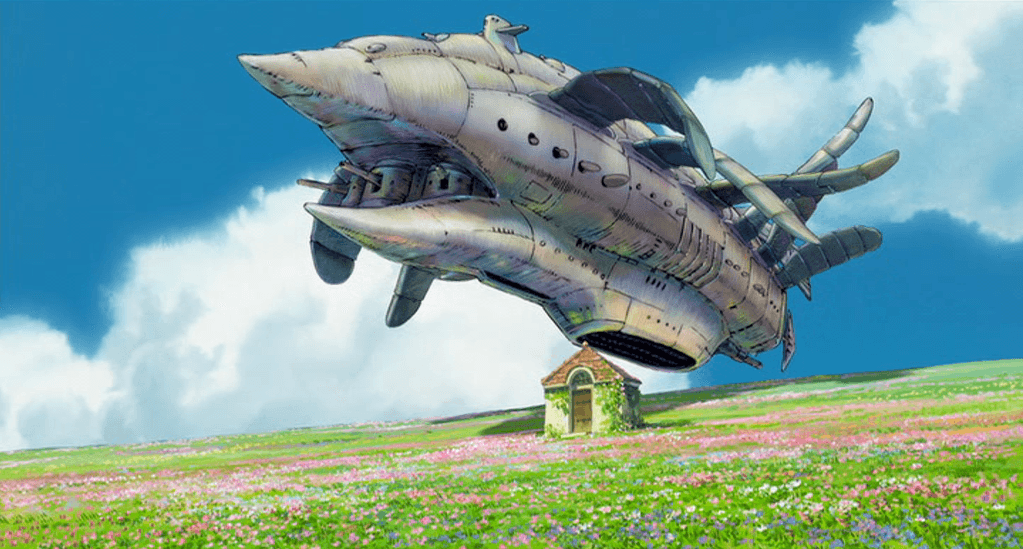

This situation is best exemplified by the way aircraft are depicted. For a start, heavy bombers are shown as powerful flying machines with a toy-like appearance. Propulsion and aerodynamics seem at best implausible. Aircraft have all the hallmarks of nuts-and-bolt engineering, and nonetheless show hatches which dilate and contract as orifices, in a disturbingly organic fashion. They carry conventional bombs as well as supernatural beings controlled by magic arts.

One of the bombers featured in the movie. A human-built mechanism with obvious animal features, it looks menacing while at the same time suggesting a kind of childish amusement. Note the contrast between its threatening grey mass and the delicate treatment of the flowers below.

Nonetheless, the moral condemnation is explicit and both sides are presented as part of an absurd tapestry of violence. This following dialogue is illuminating (emphasis mine):

Sophie: A battleship!

Howl: Still looking for more cities to burn.

S: Is it the enemy’s or one of ours?

H: What difference does it make? Those stupid murderers! We can’t just let them fly off with all those bombs.

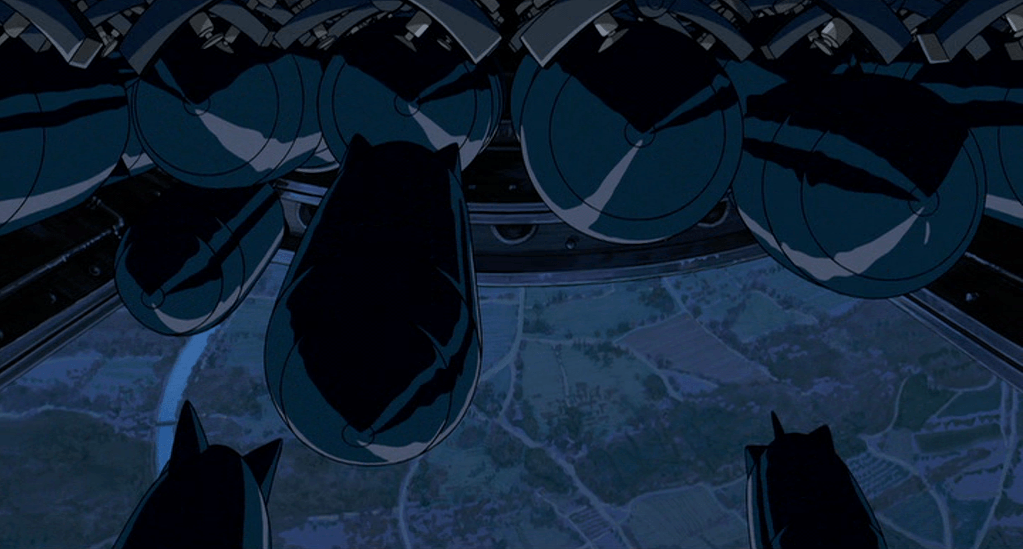

Once the tone is set, the movie rapidly shifts towards a cruder, more realistic approach. In a dramatic sequence the camera pans over a crowded town at dusk. Industrial buildings, chimneys belching out black smoke, and some barges on the river suggest a thriving manufacturing centre. The scene is dark and sinister with a sense of palpable anticipation.

The town where Sophie lives. Darkness is complete and not a single light is visible, a situation which points plausibly to a wartime black out. The place, although unnamed, has a strong Central European flavour.

Bombs are released from an aircraft flying above. Aircrew are not shown, reinforcing the idea of a brutal, impersonal force.

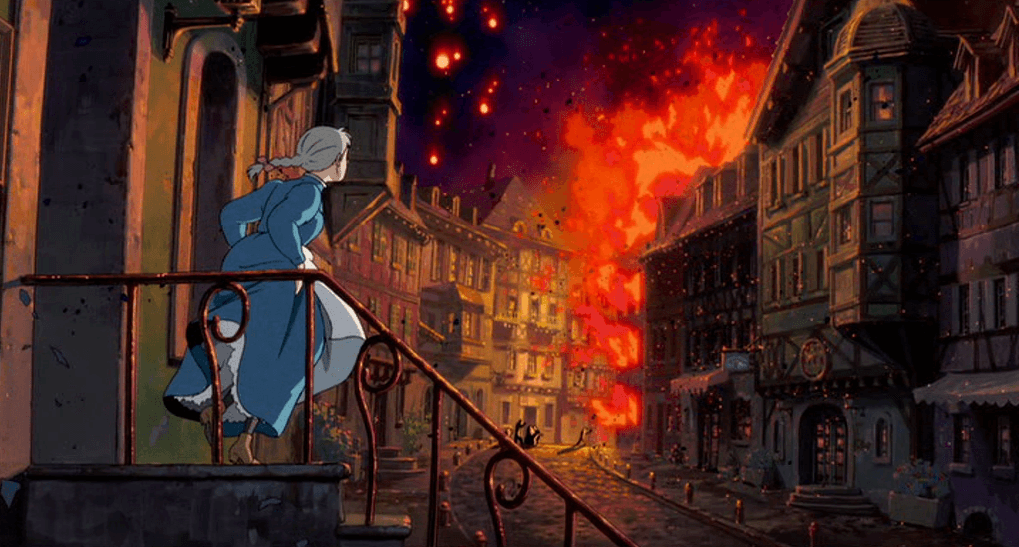

Sophie dashes outside. Almost everything has a specific connotation: bollards, cobble pavements, half-timbered buildings with oriel windows evoke irresistibly the Altstadt of any German or Austrian town. The most striking detail is the slow descent of bright yellowish orbs against the night sky. It brings immediately to mind the ominous sight of a Tannenbaum or Christmas tree, flares dropped during the initial stages of a night bombing to help mark the aiming point. A fire in a nearby building seems to be out of control while bright flames are going up in the night. The allusion to incendiaries seems compelling, a conclusion backed up by Howl’s explicit reference to “cities to burn”.

Though the movie is set in a fictional universe, the slow descent of target indicators is a precise reference to actual Bomber Command practices.

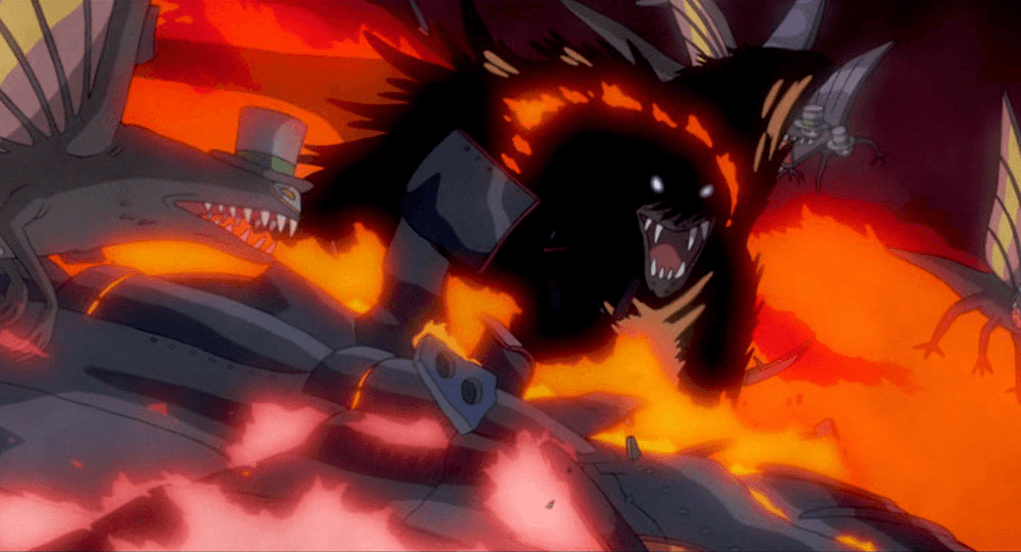

Wizards are summoned to help the war effort. Howl uses his magic powers to become a bird-like creature tasked to repel waves of enemy bombers while at the same time protecting his beloved Sophie. Night after night, it takes him more and more effort to revert to human form and his feral nature become increasingly intrusive as the battle rages. He’s finally shown as a hideous monster almost no longer human, attacking furiously an enemy bomber.

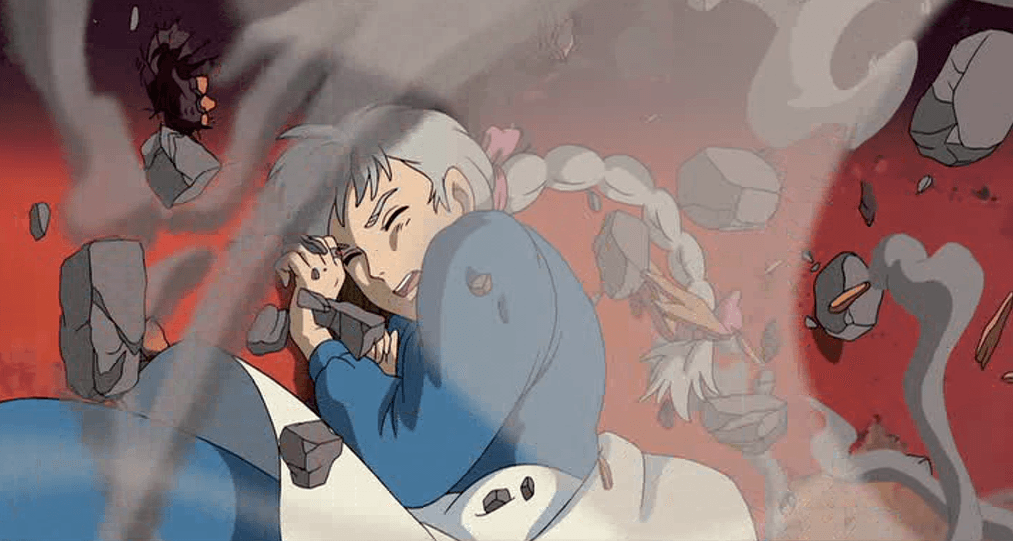

Although imaginary elements are largely prevalent,scenes showing the destructive effects of aerial bombing are strikingly realistic and match countless accounts of bombing survivors.

Multiple fires have spread out of control and the urban landscape is now an inferno, a not-so-veiled allusion to the firestorms of Dresden and Hamburg. The turbulence and the optical disturbance caused by an ascending column of overheated air have been skilfully reproduced.

Bombs blow up in a straight path, as would have happened when dropped from an aircraft in flight; some architectural features such as chimneys, gables and high-pitched roofs point unmistakably to continental Europe.

Bombing operations are eventually called off following the resolution of the main plot. In the last scene, the flying castle is seen high in the sky carrying Sophie and Howl to a long-awaited happiness, an explicit praise of simple family life and mutual love. Meanwhile, military aircraft are fleetingly shown returning to their bases.

The closing scenes contrast the new life awaiting the lovers with the absurdity of the conflict. Despite the most traditional they-lived-happily-ever-after finale, Howl’s Moving Castle has a distinct bitter taste which resonates with the many controversies surrounding the bombing war. For a start, war folly is neither recognised nor fully understood until the last sequences. Secondly, the whole destructive power of aerial warfare has been unleashed in vain because the conflict did not result in an indisputable victory – hostilities simply stopped. In both real life and fictional universes, bombing war remains a controversial issue.

Alessandro Pesaro, Digital Archive Developer

References

Arnaldi, V. (2017). Il Castello errante di Howl. Magia, mistero e bellezza nel film cult di Hayao Miyazaki. Roma, Ultra Shibuya, 2017.

Cavallaro, D. (2006). The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki. Jefferson, McFarland & Company, 2006.

Gordon, D. (2005). A ‘Positive Pessimist:’ An Interview with Hayao Miyzaki. Newsweek, 20 June, p. 67.

Smith, L. (2013). War, Wizards, and Words: Transformative Adaptation and Transformed Meanings in Howl’s Moving Castle. Available at: https://littledevil1919.wordpress.com/2013/06/27/j-anime-ghibli-war-wizards-and-words-transformative-adaptation-and-transformed-meanings-in-howls-moving-castle/ [Accessed 21 November 2017].

A questo indirizzo il materiale su Dresda:

https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/items/browse?tags=bombing+of+Dresden+%2813+-+15+February+1945%29