It is reasonably well known that some 550 aircrew and 6000 ground crew of African origin served in Bomber Command. They were a tiny proportion of the whole: the total number of aircrew in this Command was 125 000 and the figure for ground grew and other ground personnel was close to one million.

RAF Hendon’s exhibition a few years back, ‘Pilots of the Caribbean’, remembered the contribution of black aircrew – an online version is still available to view. Another very good overview is Mark Johnson’s talk in the National Archives podcast series. One of the reasons for the low numbers of black personnel, as Roger Lambo explains, is that it was RAF policy at the start of the war that black volunteers should be encouraged into the army: ‘at the time [1940], aircrew were essentially needed to man the heavy bombers. Such crews had at all times to be in the most intimate contact, and it was felt that “the presence of a coloured man in such a crew would detract from efficiency”’. [1]

As casualties mounted, however, official attitudes changed markedly: black colonial subjects were invited to volunteer and the colour bar was declared a thing of the past. Yet other stumbling blocks remained. Racial dynamics in colonies and former colonies of significant white settlement meant that avenues into the armed services were difficult, if not impossible, for well-educated black people. Again, recruits were required to be free of malaria and this was often impossible to prove. And there was a general unease about black personnel in the armed forces at a time when independence movements against Britain were becoming a feature of colonial relationships almost everywhere.

Even though the official position had changed, many recruits recounted incidents varying from discrimination to abuse at the hands of fellow personnel or civilians. Ground crew were probably worst off. When two West Africans were posted to Waddington to service the aircraft of 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron, their white counterparts demanded they were removed – which they were. They had come all this way and were made to feel very unwelcome. Officers were to some extent shielded by their status but by no means immune. Also at Waddington, Doug Rail, a Rhodesian pilot with 44 Squadron, arrived with a black rear gunner, Sgt Gus Batty. He faced considerable opposition from other Rhodesian air crew but stuck to his position that Batty was an excellent asset.[2] These examples suggest another intriguing dimension to service in Bomber Command: white colonists who volunteered were evidently fighting to defend a racially privileged social order, while black ones were fighting for just the opposite.

The West African colonies of Sierra Leone, the Gambia, the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and Nigeria were responsible for virtually all those who successfully volunteered for Bomber Command from the continent of Africa. Some applicants, frustrated at the slowness of the process at home, made their own way to Britain in the hope that they would be accepted into the RAF there. Why were they so determined? There were probably a multiplicity of reasons, but a compelling one had to do with a memory of Britain’s role in ending the slave trade and a fear of the return of slavery should Hitler win the war. The Nigerian Flt Lt Emanuel Peter John Adeniyi Thomas recalled,

My great-grandfather was a chieftain. One day his rival betrayed him to a slave dealer. He was put on a ship along with 100 other slaves and was soon on his way to America. Ten days out in the Atlantic his ship was intercepted by one of Her Majesty’s ships. The slaves were rescued, and at Freetown (Sierra Leone), my great-grandfather regained his freedom.[3]

The IBCC Digital Archive has interviewed the sons of three West African fliers who served with distinction in RAF Bomber Command: Eddy Smythe on his father, John Henry Smythe; Olu Hyde on his father, Adesanya Hyde, and Neville Shenbanjo on his father, Akin Shenbanjo.

As a child, Eddy Smythe was never really aware of how much of a war hero his father was. Born and raised in Freetown, John Henry Smythe served with 623 Squadron. On an operation to bomb Mannheim in 1943, his aircraft was badly damaged and the crew baled out. He spent the remainder of the war in Stalag Luft I; he helped others to escape but did not attempt it himself: ‘I don’t think a six-foot-five black man would’ve got very far in Pomerania’, he noted in an interview much later.[4] Within the RAF, he said that the issue of colour never came up: they were one band, fighting for one cause.[5] One thing that Eddy remembers vividly is his father starting violently and screaming when awoken, one of the effects of having been bombed by the Germans while in a training camp near Hastings.[6]

Fellow Sierra Leonean Adesanya Hyde joined 640 Squadron as a navigator. He escaped unhurt when his crew’s Halifax crashed on take-off in June 1944. A few weeks later, he took part in a daylight operation to bomb a chemical plant at Le Chatellier in northern France. Their aircraft was attacked and a fragment of flak pierced Ade Hyde’s shoulder. Badly injured and in severe pain, he continued to navigate the aircraft over the target. It was only when the English coast was in sight on the return journey that he made his wounds known to his fellow crew, accepted morphine and collapsed. He spent the next three months in hospital and returned thereafter to his squadron. He was awarded the DFC for his tenacity and devotion to duty.

His son Olu remembers learning about his father’s distinguished war record from outside, rather than inside the family. In this way, he realised how famous his father was, although he felt considerable pressure when asked if he would follow in those footsteps and be as brave. Ade came to reject violence and aggression as a solution to political problems, something that Olu shares. At the same time, he feels that the role black personnel played in defeating the Nazis should be better remembered: he finds that white Britons are surprised to learn that there were black officers in the wartime RAF.[7]

Akin Shenbanjo was one of those who made his own way to Britain in the hope of being accepted into the RAF. Of Nigerian princely birth, he enlisted in 1941 after the Battle of Britain and underwent extensive training. In fact he told the story that when he finally reached a squadron as Pilot Officer in mid-1944 and was expected to crew up, a Canadian pilot named Jimmy Watt was disbelieving of all the courses he had undergone. ‘I’ve done so much training that I could win the war on my own!’, Akin is said to have replied.[8] The two flew together in 76 Squadron throughout the war, Akin as the crew’s wireless operator/air gunner. They named their Halifax ‘The Black Prince’ in his honour. On an operation to bomb the railway yards at Lille in April 1944, their aircraft was badly damaged and they flew home on three engines; Akin was awarded the DFC for bravery. He completed two tours. Neville remembers his father coming home on leave in his smart RAF uniform, which turned heads in Leeds and made him feel ‘really good’.[10] Like Ade Hyde, Akin Shenbanjo taught his son to reject war; he felt a sense of remorse for the damage caused by the bombing.[11]

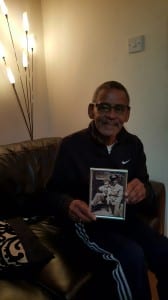

Neville Shenbanjo holding a photo of his father Akin and himself as a young child. Neville Shenbanjo Collection.

Among other West Africans whom Lambo identified as serving in RAF Bomber Command are: David Oguntoye, V.A. Roberts, N. Akinbehim, Godfrey Petgrave, Claude Foster-Jones, William Leigh, Robert Nbaronje, Bankole Oki, Bankole Vivour, Akinpelu Johnson, Valentine Oke, M.O. Audifferen, Sammy Bull, Archie Williams and Emmanuel Dadzie.[12]

Heather Hughes, Professor of Southern African Studies and Head of IBCC Digital Archive.

[1] R. Lambo, Achtung! The Black Prince: West Africans in the Royal Air Force, 1939-46’. In Killingray, D. (Ed) Africans in Britain London: Frank Cass, 1994, p. 149. The quote within the quote is from a circular letter to Colonial Governors, dated 30 may 1940 and lodged in the National Archives, Kew.

[2] R. Leach, An Illustrated History of RAF Waddington From Longhorn to Lancaster 1916-1945. Bognor Regis: Woodfield, 2003, p.147-8. Batty is identified only as a black ‘West Indian’.

[3] As quoted in the ‘Pilots of the Caribbean’ online exhibition at https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/online-exhibitions/pilots-of-the-caribbean/heroes-and-sheroes/liberator-flight-lieutenant-emanuel-peter-john-adeniyi-thomas.aspx

[4] M. Plaut interview with John Henry Smythe, 1989, Imperial War Museum. Interview 34156.

[5] H. Hughes interview with Eddy Smythe, 2 August 2017, Oxford.

[6] H. Hughes interview with Eddy Smythe, 2 August 2017, Oxford.

[7] H. Hughes interview with Olu Hyde, 30 August 2017, Malvern.

[8] Information in an email Neville Shenbanjo to Heather Hughes, 7 July 2016.

[9] Lambo, ‘Achtung!, p. 155.

[10] H. Hughes interview with Neville Shenbanjo, 30 August 2017, Leeds.

[11] H. Hughes interview with Neville Shenbanjo, 30 August 2017, Leeds.

[12] Lambo, Achtung!, pp. 145-163.