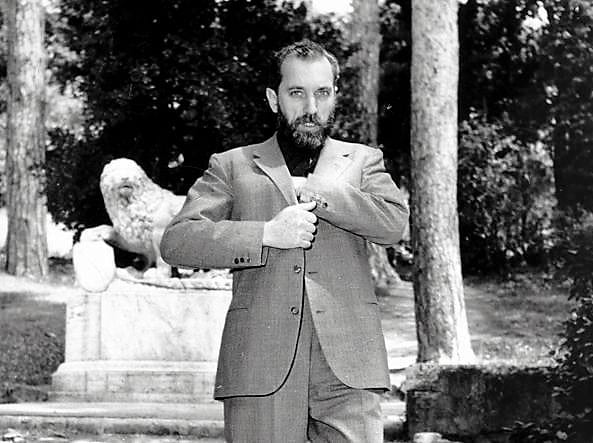

Giuseppe Berto. Unknown author, public domain. Source: https://www.corriere.it/sette/passaparola/18_maggio_17/giuseppe-berto-scrittore-la-gloria-anonimo-veneziano-3b8a419a-577c-11e8-bd9c-ca360360a9e7.shtml

Giuseppe Berto (1914 – 1978) was an Italian writer and screenwriter. Berto served with the Italian Army in Africa until he was captured and sent to Camp Hereford in Texas. There he wrote the first draft of a novel titled “La perduta gente” (The lost people) which was eventually published as “Il cielo e’ rosso” (The sky is red) in 1947.

The plot follows the trials and tribulations of a group of boys and girls from different walks of life who struggle for survival amongst the devastation of an unnamed bombed-out town. The storyline has a tragic resolution: Daniele, the son of a middle class-couple who is killed in the bombing, cannot adjust to the precarious existence of his working-class companions who have turned to theft, prostitution, and arms smuggling. Facing both loss of self and the painful awareness that evil is both universal and unescapable, he eventually takes his own life.

Berto originally titled the novel La perduta gente (the lost people), an allusion to Dante’s Inferno (canto III, v. 3). Lost souls sent to hell are deprived of God’s grace: in the same way, characters are deprived of parents, hope, and a solid moral compass.

The title later chosen by the publisher is taken verbatim from Matthew 16:2 “When evening comes, you say, ‘It will be fair weather, for the sky is red’”. Pharisees and Sadducees ask Jesus for evidence that he is the Messiah, but he gives them no firm answer. The reply reveals the limits of their understanding: they can look at the sky and predict the weather, but they cannot discern the signs of the times, i.e. events prophesied to take place in the future. Used as tile, the sentence becomes an ingenious literary device. In peacetime, a red sky can be either good or bad, depending on the context: “Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. Red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning”. In wartime, it unequivocally points to death, suffering, and destruction. Ambiguity makes the title especially intriguing: it remains firmly rooted in the New Testament and in popular culture, but at the same time points to an immediately recognisable element of aerial warfare, namely the fiery sky that follows a bombing.

This detail appears across a broad range of testimonies:

“Hull used to get most of the bombing. We could tell. If we saw a red glow in the sky, ‘Hull’s getting it tonight.’”

Interview with Geoffrey Lenthall [https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/items/show/11168]“il cielo era tutto incendiato perché era rosso” [The sky was aflame, being red]

Interview with Alessandro Novellini [https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/items/show/319]

This blogpost will be focusing on two passages of outstanding literary quality: a) the night bombing sequence, seen from the perspective of Daniele’s parents, and b) a parallel segment in which the same event is retold from the perspective of aircrews.

The most notable aspect of Berto’s writing is deliberate vagueness. The locale is not stated, although many elements suggest Treviso, his hometown. Daniele’s parents are not named. The reader surmises that the events are taking place in wartime but the exact date in not revealed. Rather than an account, the bombing becomes a symbol. It happened at no place, and still could have taken place everywhere.

Very little is also revealed about the building in which the couple lives: we only know it is a high rise one, has a central heating system, and windows are fitted with rollers rather than traditional shutters. A reader familiar with the Italian architecture of the time will immediately picture a modernist-looking house with clean lines, sober ornamentation, generous spaces, glass, polished stone – all these elements suggest an overall air of upper middle-class respectability, social standing, and stability. This is further enhanced by the fact that their son has been sent to a boarding school in the countryside.

This adds a further element of tension since aerial bombing is depicted as a totally impersonal force that wreaks havoc regardless of social standing. The fact that they live on one of the upper floors, a traditional mark of distinction and respectability, is what indirectly causes their death – the building tumbles down while they were still descending the stairs.

The attack sequence is a long, sustained crescendo of tension. Its pace remains extremely slow at first, only punctuated by sparse notations of distant disturbances. The anguish of the two characters is masterfully described: each disturbance can either be a mundane, inconsequential incident or rather the forewarning of an impending catastrophe.

The pace rapidly builds up as the events unfold and the menace of bombing becomes apparent; the rhythm of the narration becomes frantic and agitated in the last paragraphs, in which the scramble to a place of safety eventually leads to disaster when the staircase starts to crumble. The tense atmosphere is captured by a string of short, pithy sentences, with a focus on auditive and visual clues – the last image is only a mute scream of almost expressionist quality.

Berto then moves to the aircrews returning to their bases. The rhythm is now slow and the mood pensive. The men are described as cold, efficient and machine-like, almost enmeshed with aircraft. Tellingly, no one speaks but an omniscient narrator reveals that their thoughts are now with the loved ones in distant places. A key theme here is distance: aircrews are physically remote from the civilians on the ground, but also emotionally aloof.

Overall, Berto’s anti-war sentiment remains measured. There are no tirades, invectives, or explicit condemnation of the bombing war but rather a vivid denunciation of the plight of civilians in wartime and the impersonal, mechanistic nature of aerial warfare. This is further reinforced by multiple references to the stars high above, indifferent to human plight. Evil, as Berto explicitly suggests in the last sentences, is at the same time universal and enormous, therefore unescapable. Moral reasoning falls upon the reader – the writer’s task is only to represent life without omission or embellishments, as it truly is.

Excerpt one. The attack sequence

The man was shaken out of his sleep the moment the siren began to sound. He heard the three warning blasts from the tower, which was not far off. One had the impression that the sound was a material thing that travelled a long way, like wave circles in a piece of still water.

He tried as hard as he could to lie still. Absurdly, he hoped that his wife had not awakened. But she spoke almost immediately, in the darkness. ” That’s the warning, isn’t it? ” she asked.

” Yes,” he answered; and they lie still and silent for some time, listening to every sound.

They heard a train over in the direction of the station; it gave a whistle, and then another, much longer. Then the engine snorted laboriously.

” Listen to how slowly it puffs,” said the woman.

” That’s because it’s getting under way,” said the man. “It must be a goods train.” The snorting of the train became more and more hurried and farther and farther away, and then ceased.

Again the man and the woman lay still and silent in the darkness, waiting for noises; but they did not hear any. There were, of course, one or two ordinary noises, such as the creaking of the furniture and a buzzing in the water-pipes or somewhere, but these did not enter into their conscious thoughts because it was not for that kind of noise that they were waiting. Something might come from outside, and they lay in expectation of that, although they thought that it would not come.

Then the man fumbled about on the bedside table, round the lamp which remained unlit. He struck a match and looked at his watch. “It’s not one o’clock yet,” he said.

” Let’s hope it won’t last long,” said the woman. ” Otherwise you’ll be tired to-morrow at the office. For some days now you’ve been tired all the time.” ” There’s a lot to do at present,” said the man. Before the match went out he had lit a cigarette. He tried to concentrate on the variation of brilliance in its glowing tip each time he breathed. But he was unable to take his mind off the things that might be going to happen.

The woman could not stay still for long. He heard her get out of bed and move about as though looking for something.

” Do you want me to light the candle: ” he asked.

“No, a match will do,” she said. “I can’t find my dressing gown.” He lit a match and saw her in her long white nightgown.

She found the dressing-gown at once. From the way she moved, you could tell she was nervous

The match went out, and they were in the dark again.

“You’re always nervous when the warning goes,” said the man. ” You mustn’t be so nervous. There’s no danger here.” ” It’s not on our account that I’m frightened,” said the woman. ” You know I always think about him, at these moments.” The man smiled. ” Be reasonable, my dear,” he said. ” We sent him away to school to make our minds easy, and yet you’re always worrying about him.” “Yes, I know,” she said. ” But it’s beyond my control, and I don’t know what to do about it. It’s not that I’m really afraid, you see. I don’t quite know what it is I feel. I should like us all to be together when there’s any danger, that’s all I want. Then if anything happened to him, it would happen to us too.” The man did not answer. All he said was: ” The war will come to an end soon, let us hope.” ” Yes, let us hope so,” said the woman. Then she went to the window and pulled violently at the blind-cord. As it went up, the blind creaked in the silence, and somewhere, perhaps, somebody started at the sound it made.

The flat they lived in was high up, on the fifth floor of one of the new “skyscrapers”. From the window the woman looked far out across the plain, towards the little village where her son was at school. In that direction, thank God, everything was dark and quiet. Of course it was silly to be frightened. They would never go and bomb such a small village.

From below came a noise of people walking by, talking loudly. She could hear it quite well although it was so far below, and they must be soldiers because they made such a noise with their boots. The woman looked down, but of course could see nothing, only the darkness; but she pictured the soldiers to herself as they walked by, talking. She imagined they were full of gaiety, poor devils.

Then the soldiers went round behind the house towards the Cathedral, and though she could not hear them any more she went on looking.

All that darkness below was the Sant’ Agnese quarter a lot of roofs piled up on top of each other, with a few new tiles here and there amongst the old, and amongst the roofs the queer, narrow cracks that were the streets. Beyond was the church, so high that it looked lonely in the midst of the houses. She could not see it, but she imagined it. Further away again were the walls, and the station, and behind them the houses in the outskirts of the town gradually merged into the grey-green of the country. And away beyond there was a small village which she could not see clearly even in the daytime, because it was too far off. There her son would certainly be sleeping, for the sound of the siren did not reach so far. High above everything else were the stars and the quiet night.

” Get back to bed, my dear, you’ll catch cold,” said the man’s voice behind her.

She turned her head slightly. ” Let me stay a little longer,” she said. “It’s so lovely.” She was calm now. All she felt was a slight exaltation in her blood and in her brain, a sense of well-being which came from the air that smelt of the river and of spring, from the night and the gentle wind, and from her own thoughts that were in harmony with these things.

Another sound came up to her from below, beginning a long way off. It was a motor-bicycle, which was going slowly because of the darkness but was making a great deal of noise.

A noise so loud radiated widely over a large area. The people in the houses trembled at the sound, and even after they had recognized it for what it was they had difficulty in recovering their tranquillity

It must be a military motor-cycle without a silencer. Goodness knows where it could be going at that hour. The noise came slowly nearer. The motor-cycle passed the house and went on beyond it, and the noise continued to be heard, varying in quality as it reverberated among the houses.

The noise lasted for perhaps three minutes, and after that still continued in the air, with a different quality; but the woman did not understand, because she was not thinking about it.

Every moment the new noise became louder and more different.

Then the woman looked up at the sky above the town and realized that it was coming from up there. Certainly it must be a friendly aeroplane, since it seemed to be all alone, and yet she began trembling all over and could neither move nor speak.

All she could do was to look. Suddenly she saw a cluster of white lights which took shape and remained hanging in the sky. They seemed to rock faintly in the air.

The man, who was looking towards her, suddenly saw her figure stand out darkly against the light outside. He rushed to the window. He saw the whole town lit up, and in the sky the cluster of white lights, and then another cluster that was just taking shape. Engines were humming, very high up.

From a roof over in the direction of San Sebastiano a machinegun began to fire red-hot tracer-bullets towards the clusters of light. The bullets rose one behind the other, slowly, it seemed, and slower still, and died with a little explosion.

” Come, let’s go,” said the man, troubled.

But the woman was looking and could not move. She felt indeed that her legs were incapable of movement. Over the whole sky the light was increasing, and the noise of the engines.

” Come on, hurry up,” cried the man, shaking her, and he seized her by one arm and dragged her outside towards the staircase. The lift shaft was empty, useless.

They started to go downstairs. On one of the lower floors a woman screamed someone’s name several times in an agonizing manner, and then was silent. Footsteps also could be heard down below, and doors banging. From the skylight came a luminous whiteness like moonlight, but brighter and more diffused and throwing hardly any shadow. In a light so white everything had an evanescent, alien look

They went down a few steps. The woman walked with difficulty and the man went close beside her, supporting her.

Meanwhile the sounds outside became louder. Hundreds of engines were in the sky over the town. Then, in addition, came the sound of falling bombs, like something sucking in the air in a horrible fashion

The woman realized at once that they were bombs, although she had never heard a noise like that before. It seemed to be right above her head and it became more horrible every moment.

First she felt a rush of wind on her face and heard glass breaking, and then every other noise was drowned in the explosion of the bombs. The house shook and the stairs rocked under her feet

She stopped and leant her back against the wall, her arms outstretched.

She gazed at the man imploringly, with dilated eyes, her mouth wide open so that she looked as if she were screaming.

The man shouted something that was lost in the din, and shook the woman and struck her. She clung to the wall with all her strength, and all the time she looked at him imploringly.

The man made as though to lift her in his arms, but he could not, because now the house was reeling beneath him. Then he too leant with his back to the wall and took the woman in his arms. She suddenly lost all her rigidity and abandoned herself to him, panting, her eyes closed. Ah, that was better, she thought; now she would not mind anything. He held her tightly as though trying to protect her, and he was quite calm, because he had never loved her so much in all his life.

The last thing of which he was conscious was a hot wind which came up from below and lifted them up against the wall; and the wall at his back slowly, slowly gave way, till it no longer supported them.Berto, Giuseppe (1948): The Sky is Red. Translated by Angus Davidson. London: Secker and Warburg, 48-52,

Excerpt two. Back to base

Berto, Giuseppe (1948): The Sky is Red. Translated by Angus Davidson. London: Secker and Warburg, 61-63.

Hundreds of planes had flown a long distance during the night in order to reach the little town. Inside each plane was the crew, every man with his own job-pilots, observers, radio operators, bomb-aimers-highly trained specialists, reliable, efficient.

The men think as they fly through the night. Underneath is the dark earth, and nothing can be seen. Above are the stars, and the stars help a man to think. As they fly through the night, these men have thoughts of far-distant things, of places in another part of the earth, places to which they belong and to which they hope to go back some day. There exists in them an immeasurable longing to go back home, a longing which makes them a little melancholy but which is at the same time their shield against the difficulties of life. Always, whether in weariness or pain, they think about going back home.

As they approach the town, the men abandon their thoughts of distant things. The planes get ready for the bombing.

Formation, timing, target-sighting. They are all easy in their minds because it is an easy job which will not spoil anyone’s chance of going back home.

A light aeroplane has gone ahead and has dropped clusters of parachute flares. The others take their direction from these flares. From the ground one or two machine-guns have started, quite ridiculously, to fire at the flares. Their bullets rise in a continuous string and die in mid-air.

The observers look down and recognize the places they have studied on their maps at the briefing. They are now following the railway. In front can be seen the station, about the size of a packet of cigarettes, with its marshalling yards and its railway bridge. A little further on there should be the iron bridge over the river.

Now they are ready. All on board are conscious of a moment of tension. The planes are over their target

Their target is a station, a railway bridge, another bridge, some marshalling yards. From up above they look like children’s toys, these things that have to be. destroyed because the enemy is using them for purposes of war. But all around, and close beside them, there are other things which also look as small as children’s toys. These are the houses of the town, which are not marked on the maps with the special signs that are used to pick out the target. They are therefore ignored, and it is as though they were not there.

Another thing that is ignored is that inside these houses live people, large numbers of people. The little town has, perhaps, more than a hundred thousand inhabitants, now that so many refugees have come there from the neighbouring cities. More than a hundred thousand people are smitten with terror. They have seen the flares and heard the engines, and have understood.

But the others, up in the sky, do not think of that. They know nothing of the people they are preparing to kill. They do not know how they speak or how they live, with what hopes and witl1 what miseries. They have never seen a single one of those hundred thousand people.

They are people who speak with an ancient grace, who aspire to a leisurely, quiet life, who are no longer able to accomplish much, whether from hatred or from love. For the moment they are content merely to live, merely to reach the end of the war alive, so that they may live better afterwards. And the hopes of many of them, for a better future, are centred precisely upon those men who are waiting, tensely, in the moment before they touch the levers.

The men in the sky know nothing of all that, and they do not think of it. They too, when they picture their own lives, picture them as leisurely and quiet, with a nice house and the right sort of work and people round about with whom they can live in peace. And yet a universal evil has given them the power to kill unknown people, people very like themselves.

An evil so enormous that, because of it, they bring terror and death and destruction without thinking about it, with the consciousness of performing a duty.

Their hands make only a simple gesture to move the levers.

The bomb-doors under the fuselage open, and the bombs slip out into the air. They cannot hear the noise the bombs make as they fall.

The planes drop their bombs in formation, and each formation is very wide, covering the station and many houses round it.

The men who have pulled the levers look anxiously down, watching the sudden flashes of the explosive bombs and the luminous bursts of the incendiaries. The hits are well concentrated in the neighbourhood of the target.

The formations make a wide circle and return over the town.

Even the ridiculous machine-guns have stopped firing now.

Down below there is a cloud of dust and smoke through which the fires and the bombs which are still bursting can scarcely be seen. The station, the railway lines, the bridge, all are covered by the cloud, which the light of the flares does not succeed in penetrating. They drop their bombs into the middle of it. With such a large number of bombs dropped over such a wide area, the target must surely have been hit.

Now they are on their return journey. For many miles they can see behind them the glow of the burning town. The men feel satisfied. No anti-aircraft fire, no night fighters, a mission well accomplished. For a certain time the enemy will not be able to make use of the station, the railway lines, and perhaps the bridge, if it was hit. And if, in order to achieve this, they have produced a sum of human misery that nothing on earth, even the greatest good, can ever wipe out, that is a thing that has no importance. They do not think of it, and it is not their fault, because of the universal evil.

In a short time the glow of the fires is lost in the distance, and the men fly on under the stars.

And the stars fly too; they fly at a fantastic speed towards the places to which those men belong, in another part of the earth. In a matter of a few hours, the stars which are now above their heads will be above Kentucky, Missouri, California.

And each of those men who have destroyed houses and human creatures can still think lovingly of other houses and other human creatures.

Literature

— Berto, Giuseppe (Enciclopedia Treccani). Available online at https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giuseppe-berto_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/, checked on 4/11/2024.

— Giuseppe Berto (Encyclopaedia Britannica). Available online at https://www.britannica.com/biography/Giuseppe-Berto, checked on 4/11/2024.

Pullini, Giorgio (1988): Berto, Giuseppe (Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 34), checked on 4/11/2024.

Sabatini, Gabriele (2017): 7 voti allo Strega del 1947 / Il cielo è rosso di Giuseppe Berto. Doppiozero. Available online at https://www.doppiozero.com/il-cielo-e-rosso-di-giuseppe-berto, updated on 7/5/2017, checked on 4/11/2024.