This year sees the 80th anniversary of events that took place in 1944. We can expect the commemoration of events such as the Great Escape, D-Day and the first use of V-weapons. Some events of the strategic bombing campaign of 1944 will be remembered too. Bombers played an important part in the preparation for Overlord and the allied advance to liberate occupied Europe. Visiting the IBCC, you can discern the battle fronts advancing through France and Italy by watching the movement of the bombing line on the large animation of the bombing war in the exhibition space.

In public memory, the most commemorated (or contentious) bombing operations tend to be the ones that are perceived as the most daring, together with those with the highest death rates in the air or on the ground. Operation Chastise to breach the dams of the Ruhr, the 8th Air Force’s Schweinfurt mission, and the firestorms of Hamburg in 1943 or of Dresden in 1945 are frequently referred to. This year for RAF Bomber Command, we can expect the anniversaries of the sinking of the Tirpitz and the operation to Nuremberg to be highlighted in the press and on social media. More RAF airmen were killed on the operation to Nuremberg 30/31 March 1944 than during the four months of the Battle of Britain. On that one night, 95 aircraft were lost and 545 airmen were killed. You can read about it in several books including Martin Middlebrook’s Nuremberg Raid (1973) and John Nichol’s The Red Line (2014). I intend to blog about the way the memory of this operation has fed into the heritage and cultural memory of Bomber Command next month.

However, RAF Bomber Command lost 78 aircraft and 438 aircrew killed on their attack on Leipzig the month before, but because the aircrew losses were eclipsed by Nuremberg, I do not expect to read much about it elsewhere this year. Of course similar acts of bravery, sacrifice and shared suffering occurred during every bombing operation, in the air and on the ground, regardless of how well remembered it might be.

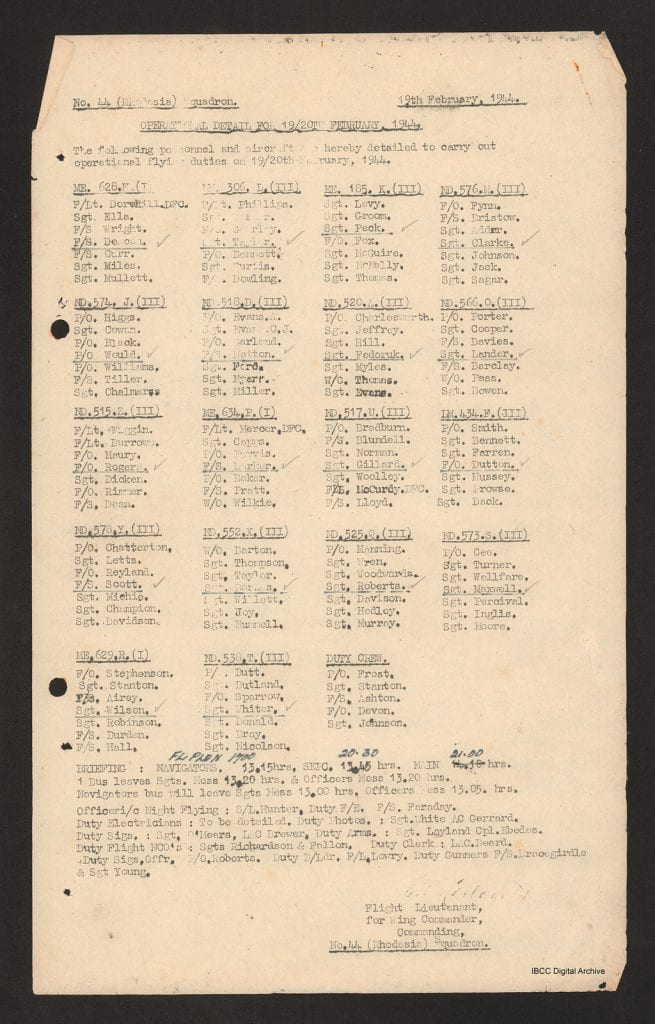

44 Squadron operation order for 19/20 February 1944.

On 19 February 1944, 823 aircraft took off from stations in England to bomb Leipzig. 44 Lancasters and 34 Halifaxes failed to return the following morning. Four aircraft were lost by collision and around 20 to anti-aircraft fire. The majority were shot down by Luftwaffe night fighters. The German fighter controllers sent only a few aircraft to the diversion minelaying at Kiel. Engaged by fighters as soon as they crossed the Dutch coast, the bomber stream was under attack all the way to the target.[1] Air gunner, Robert Creamer reported seeing three Lancasters shot down.[2]

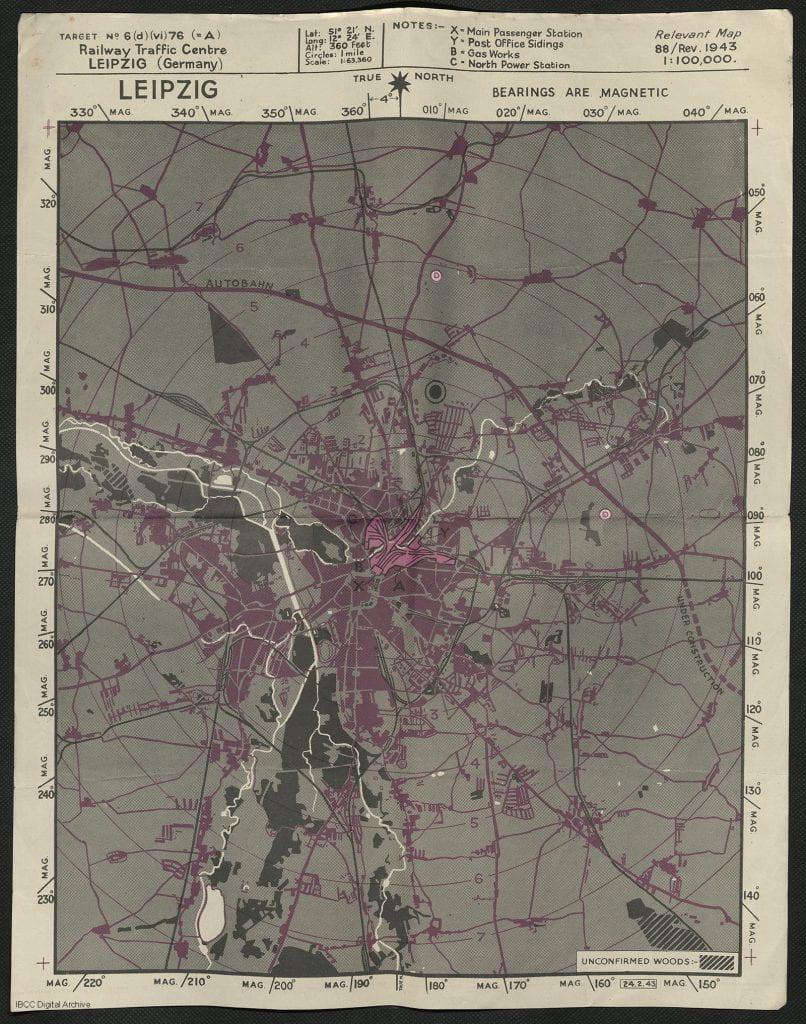

H2S map of Leipzig

Due to unexpected winds, some crews arrived before the Pathfinders and had to circle the target. Leipzig was obscured by cloud and the Pathfinders used sky marking. Over 80 USAAF aircraft were dispatched to bomb Leipzig the following day. It is impossible to differentiate between the damage caused by the British or American bombing in the subsequent reconnaissance photographs. However, for the people in snow-covered Leipzig, it didn’t really matter who dropped the bombs. Almost 1,000 people were killed on the ground.

The IBCC Digital Archive contains over 70 items about this operation. Whether in the air or on the ground, for families, it is the bombing operations their loved ones were involved in that are remembered.

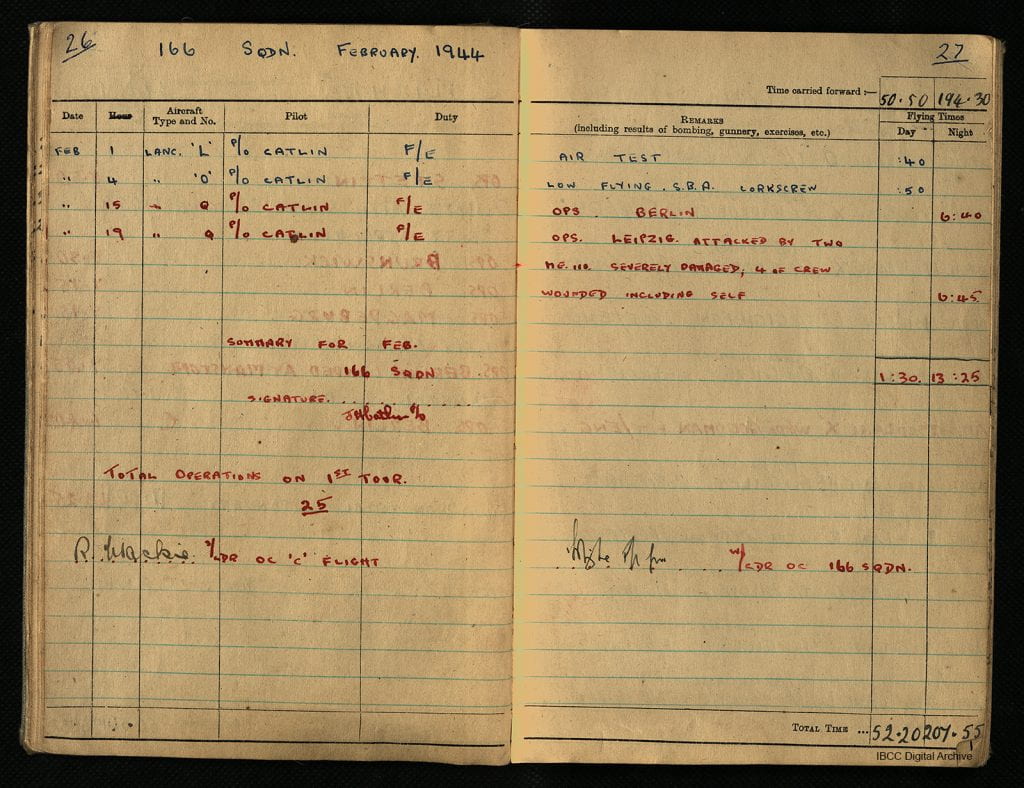

The story of the crew of Lancaster LM382 deserves to be told. Pilot Officer James Catlin, and his crew, Sergeant Barry Wright, Pilot Officer F Sim (RCAF), Pilot Officer A Pragnell, Sergeant Thomas Hall, Sergeant T Powers, and Sergeant William Birch, took off at 23:40 with 21 other 166 Squadron aircraft from RAF Kirmington. After a couple of ‘uneventful’ hours in the air, they were attacked by two ME 110s over Stendal, Germany.

A page from Barry Wright’s log book. Leipzig was his 25th operation. Ten had been to Berlin.

“In the first attack the electrical system was fused and all lights in the aircraft came on. The mid-upper gunner was badly wounded and the rear turret damaged. Rear and mid-upper gunners both fired long bursts and the enemy aircraft was last seen going into a dive with smoke pouring from it… The other aircraft then came into the attack and closed to 40 yards range… Both gunners fired long bursts and hits on the enemy aircraft are claimed. The attack was then broken off.”[3]

James Catlin’s account contains more detail. After the first attack, “aileron control was lost and it was only possible to apply left rudder… the R/G [rear gunner] was heard to give a good commentary, but the pilot was unable to carry out the manoeuvres ordered.”[4] Catlin gave the order to prepare to bale out but cancelled it when it was discovered that the mid-upper gunner was unconscious and could not be removed from the turret. The bombs were jettisoned at 03:30. The wireless operator managed to put the lights out by removing the fuses and the navigator plotted a course for home. Although he was badly wounded and fainted several times from loss of blood, Barry Wright, the Flight Engineer, transferred fuel from damaged petrol tanks and kept the engines running. They crash-landed at RAF Manston at 06:05.

Pilot, James Catlin later wrote to Wright’s mother, telling her “Now I want to be quite honest and frank when I tell you that we all owe our lives to Barry. Although wounded and on the point of collapse, he would not leave his post”. Wright spent time at RAF Hospital Halton before returning to flying in April 1944. He later received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, Catlin was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and Sergeant William Birch the Distinguished Flying Medal.[5]

In 1944, Catlin and Wright’s experiences on the Leipzig operation was important news. It was used as morale boosting propaganda with headlines such as “CRIPPLED BOMBER, LIGHTS FULL ON, WON DOG-FIGHT.”[6] The war rhetoric carefully omitted the unsustainable 9.4% losses. However, eclipsed as it has been by the even greater RAF losses on the Nuremberg operation, unless this blog post is read, I doubt many people will think of the Leipzig operation this February.

References.

Middlebrook, M and Everitt, C. (1985) Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference book 1939 – 1945, Viking.

The National Archives, 166 Squadron ORB Records of Events Feb 1944 AIR 27/1089/29

The National Archives, 166 Squadron ORB Summary of Events Feb 1944 AIR 27/1089/28

Wright, Barry Colin collection IBCC Digital Archive https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/show/1587

[1] Middlebrook, M and Everitt, C. (1990) Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference book 1939 – 1945, Penguin, p. 473.

[2] RA Creamer, “Robert Creamer’s Operations and Wartime Memories,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed February 6, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/26388.

[3] The National Archives, 166 Squadron ORB Summary of Events Feb 1944 AIR 27/1089/28

[4] J H Catlin, “Captain’s account of operation to Leipzig in February 1944,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed February 6, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/26765.

[5] “Extract from London Gazette 17 March 1944,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed February 6, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/26794.

[6] “Four newspaper cuttings,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed February 6, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/26768.