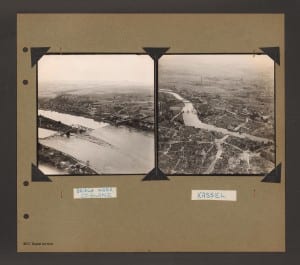

By 21 March 1945, Kassel had been the target of 40 air raids. A model, commissioned just after the end of the war and exhibited in Kassel’s Stadtmuseum, shows what the city centre looked like in May 1945:

The Royal Air Force had already targeted Kassel for a massive attack on 3/4 October 1943 but the target indicators had been set wrongly so that the bombs mostly missed Kassel but destroyed a number of villages to the east, Sanderhausen among them. On the second attempt, on 22/23 October, over 500 aircraft did not miss and created a firestorm which destroyed most of the old town which consisted mainly of half-timbered houses (the area in the foreground of the picture). The old town was densely populated and had narrow thoroughfares in which fire could spread easily. There were some public air raid shelters but mostly people had sought protection from the bombs in the cellars of the buildings where they lived.

The experiences of people who survived that attack were collected between 3 February 1944 and 21 July 1944 by Dr Paetow, Director of Office for Missing Persons in the City of Kassel. (The last record is dated 22 October 1944 but a note by the editor suggests that this is a typing error.) It is not clear what motivated Dr Paetow or how he selected his eyewitnesses but their addresses suggest that they lived mainly in the old town and the city centre or that they were at work there during the attack. These statements have been translated from the German for the IBCC with the help of Tricia Coverdale-Jones.

The format of the statement seems to have been modelled on witness statements given to the police although it is not clear how they were recorded originally. They give the name or names of the witnesses, usually their date of birth and occupation or rank (in civil service or occupational terms). Their value lies in the fact that these statements are fairly immediate to the events although it would seem to me that the later ones are more fluent than the earlier ones and also more elaborate.

Record 70, for example, tells the same story twice, once without date, fairly short and sparse, whereas the second version is much longer, more detailed and also much smoother and fluent in its description. The later records also tend to take more account of the aftermath of the raid and record 75 seems to imply a number of criticisms to the effect that overlapping jurisdictions led to disorganisation and hindered the burial of the casualties of the raid.

Record 75 also mentions the mistreatment of Italian military internees by the SS but during the raid, differences of nationality seem not to have made much of a difference. Record 20 is the statement of a Dutchman who lived through the event but records 31 and 89 also refer to Dutch workers. French workers and prisoners of war are mentioned too a number of times and record 36 is in fact an account by a Frenchman; the content of the statement would suggest that the person listed as the witness functioned rather as an interpreter.

The accounts are mostly sober and emotions are implied rather than openly addressed. Little is said about the pilots and bombers (“Churchill got everything, the bastard!” (record 70) is a rare exception) but even the loss of close relatives is stated plainly. This seems to have been an expectation at least of the person recording the interviews as a note has been added to record 35. Mr Mootz gives the impression that he cannot let go of the pain of having lost his happiness. At every sentence, he bursts into tears. His arm is also still paralysed in part. I therefore had to get his wallet out of his pocket as he wanted to show me pictures, the last remnants of his lost happiness. He obviously needs to talk about his misfortune and although he bursts into tears, this seems to give him relief. I think he’ll be well again in a few months. Physically, he appears to be quite sturdy. It is therefore even more surprising that he is so depressed.

This is a statement about a man who had just reported the loss of his wife, his daughter, his daughter-in-law and several grandchildren. He had also stated that he had lost one son in the war and two more were seriously ill as a result of the war.

Together, the records show that it was the fire which killed the majority of people. Shelters and some cellars had been equipped with ventilation pumps but their purpose was to suck in fresh air from the outside. As the fires raged, however, the pumps were sucking in smoke and fumes. A number of survivors state that they fell asleep in these cellars (meaning, I think, that they lost consciousness) and people were then killed either by suffocation or by the heat. Record 88 states that people going through cellars after the raid thought that they had found kohlrabi under rags but it turned out to be the browned skulls of the people who had been incinerated there.

In some places, the heat must have been so intense that crystal glasses had melted into blobs (record 70); according to The Sunday Express of 24 October 1943, “the flames rose up 4,000 ft.” People did, nevertheless, feel safer in the cellars rather than braving the firestorm and collapsing buildings outside.

The collection of statements includes testimony from people of various ages and backgrounds and of both sexes. Compared to more recent attempts at collecting evidence regarding this event and similar ones in other towns and cities, they have the advantage that also the voices of those can be heard who were already older at the time. Despite the use of terms such as ‘night of terror’ and ‘terror attack’, these accounts can be assumed to be less mediated and coloured by later accounts as there seems to be little that is formulaic in them or that suggests an emerging shared narrative. They therefore complement the interviews of bomber crews and are made available by the IBCC.

Harry Ziegler

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010001](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010001-300x250.jpg)

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010002](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010002-199x300.jpg)

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010003](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010003-201x300.jpg)