Alfonsino ‘Angiolino’ Filiputti was born in 1924 at San Giorgio di Nogaro, a small town in the Friuli region of Italy. A promising painter from childhood, Angiolino was initially fascinated by marine subjects but his parents’ financial hardships forced an end to his formal education after completing primary school. Thereafter, he took up painting as an absorbing pastime.

When the war broke out, Angiolino depicted some of the most dramatic and controversial aspects of the conflict in a style characterised by frankness, flat rendering style, bold colours and a rudimentary expression of perspective. Events reported by newspapers, broadcast by the radio or spread by eyewitnesses, became the subject of colourful paintings, in which factual details were embellished by his own rich imaginings and sometimes intertwined with fictional details. Each work was accompanied by long pasted-on captions, so as to create fascinating works in which text and image were inseparable. Many visual elements of his work alludes to the time-honoured tradition of cantastoria (lit. ‘story-singer’), who would tell stories in public places to whoever gathered around, while gesturing to a series of images produced by the ‘story-singer’ for this purpose.

20 August 1944. Big formations of RAF aircraft en route to Bavarian targets, hindered by batteries based at Grado. San Giorgio di Nogaro, Udine province. Tempera on paper. Four aircraft have been coned by searchlights amidst scattered bursts of shells. The countryside is an indistinct mass of darkness, highlighted by sparse yellow highlights.

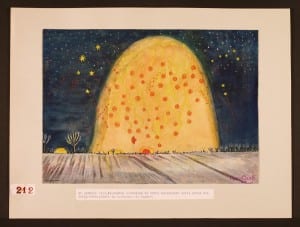

20 January 1945. Early night attack on the city centre of Udine, as seen from San Giorgio di Nogaro. Tempera on paper

In striking contrast with the serene and peaceful night sky, the composition is dominated by an ominous yellow glow with red dashed lines of anti-aircraft fire. Ghoulish mulberry trees, a common feature of the Friuli rural landscape, are silhouetted against the fires.

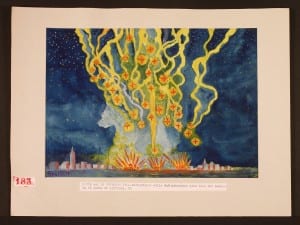

10 November 1944. RAF bombers attack the Latisana Bridge guided by target indicators.

Tempera on paper.

The slow, inexorable descent of target indicators is skilfully contrasted with bursts of the first explosions amongst buildings illuminated by a sinister reddish light. The bridge is merely hinted at, and the Tagliamento river is barely discernible in the bottom right corner.

This corpus is an extraordinary account of how the war was translated into images by a young man of Friuli, who allows us to tap into the popular society of wartime Italy. He explored a broad range of subjects, including the sinking of the SS Conte Rosso by HMS Upholder (P37), the Laconia incident (a series of events surrounding the loss of the eponymous British troopship) and well-known Bomber Command operations such as the bombing of Dresden and the attacks of the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams led by Victoria Cross recipient Guy Gibson. Other works focus on Nazi brutalities, the deeds of the resistance movements, as well as civilian life in wartime Europe: bomb disposal units and British evaders being helped by civilians. The emotional intensity of the events depicted emerges strongly from each image, in striking contrast with its simple, unaffected and unsophisticated treatment. After the war, however, interest in his work declined and Angiolino grew increasingly disenchanted as he lamented the lack of recognition accorded his art, of which he was proud. He died in 1999, resentful and embittered.

The aestheticisation of violence has been the subject of considerable controversy and debate for centuries. On top of that, Angiolino’s art was never intended a mechanical translation of reality into a durable medium – his temperas where intended to engage society and to influence it. For instance he translated into rich images the actions of Partisans, in doing so preserving the memory of the struggle for liberation and protecting it from misrepresentations, downplaying or illegitimate appropriations. The temperas may prompt further exploration of the complexity of our attitudes toward war and conflict and may offer historians and sociologists new perspectives on the meaning of violence in the context of the mass conflicts of the 20th century, indicating that what may be unproblematic in one victorious country was difficult and controversial elsewhere. The collection is probably unique in Italy and there are few comparable examples in other countries in continental Europe.

The IBCC Digital Archive would like to express gratitude to Anna and Stefano Filiputti, the children of Angiolino Filiputti; Alessandra Bertolissi, wife of the late Pierluigi Visintin the art critic who rediscovered Angiolino’s work; and Pietro Del Frate, mayor of San Giorgio di Nogaro, where the temperas are now on permanent display.

Alessandro Pesaro, Digital Archive Developer