Editors’ note

Federica Lampugnani got in touch with the University of Lincoln during an IBBC Digital Archive presentation at Parco Nord Milan – her dissertation on the bombing war in Milan and its subsequent memorialisation immediately aroused interest. We are delighted to publish a summary of her dissertation in form of a blogpost. Needless to say, we wish Federica every success in her future career.

Federica Lampugnani

The IBCC Digital Archive Team

Introduction

This blogpost summarises the findings of my dissertation – EUMM e il bunker Breda. La patrimonializzazione della memoria storica nel Nord Milano (EUMM and the Breda shelter. Turning historical memory into local heritage in a Milan northern district. It was submitted in fulfilment of the Cultural Anthropology programme I attended at Bicocca University in Milan (Italy) from 2016 to 2019.

Its goal is to shed light on the many-faceted memory of the bombing war in a Milan northern district, researched from the standpoint of cultural anthropology. Fieldwork was carried out over two years, from September 2016 to January 2019. The aim was to demonstrate how a certain type of recollection, linked to the memories of the air raids of the Second World War, has been understood, lived, and reinterpreted by different social actors.

Post-remembrance

“I am, sadly, extremely pessimistic when people ask me «What will happen when all of you will be dead?». This is despite having spent the last 30 years of my life talking about Auschwitz. I think that a few years after the death of the last of us, the Shoah will initially be a chapter in a history book then a few lines and eventually even that line will disappear”

These were the words of Liliana Segre, lifelong senator (e.g. member of the Italian upper house of parliament) and Auschwitz deportee, who recently voiced her thoughts on Holocaust remembrance.[1] Loss and oblivion seem to pervade modern society. Faced with this sense of looming loss, scholarly enquiry has focused on the way remembrance and post-remembrance can turn memory into cultural heritage. My university background has allowed me to see remembrance from an historical point of view, especially when it comes to analysing Holocaust Remembrance Day and Shoah memorialisation through the lenses of political institutions.[2] With this research I have tried to show how Ecomuseum’s approaches can be framed as an anthropological process hinged on the shelter, which sits at the intersection of symbolical and tangible memories.

The shelter

The Breda Factory bomb shelter was built during the Second World War in the Sesto San Giovanni district of Milan. Originally used by workers of the fifth section (aviation), it is now located in what later became «Parco Nord», a vast, managed green space. In 2009, when the EUMM – Urban Metropolitan North Milan Ecomuseum was founded, the shelter was given a second lease of life thanks to the creation of a permanent exhibition. This undertaking is part of a broader landscape of actions carried out by the Ecomuseum in its northern Milan catchment. Their immediate purpose is to foster urban regeneration and the preservation of the collective material and immaterial memory – the overarching aim is to transform them into collective heritage.

Field research has been essential for me. It has indeed allowed to live ethnographically the process of creating cultural heritage from historical memory. My methodology has been Clifford Geertz’s hermeneutical circularity, a respected approach highly influential in the anthropological studies field. According to Geertz, the knowing subject is not a neutral entity, but rather a historically-situated one, shaped by their own culture and knowledge. This circularity brings the subject and the knowing object to a reciprocal interaction.[3] It became clear that my own point of view would be bounded by that. Even more, it would be the locus of a continuous negotiation between mine and other points of view. Within this circularity of knowledge and meaning, the practical aspect of the lived experience was especially relevant. This is influenced by the spatial-corporal data underpinning the incorporation studies of Pierre Bourdieu and Thomas Csordas.[4] I decided to take into account these methodological approaches after multiple visits to the shelter. The emotional and sensorial stimuli, the attention to the use of the body in a closed and hostile environment, plus the atmosphere of a 70-year old underground shelter were the most efficient approaches to communicate bombing war heritage and its contested dimension.

The bombing war in Italy

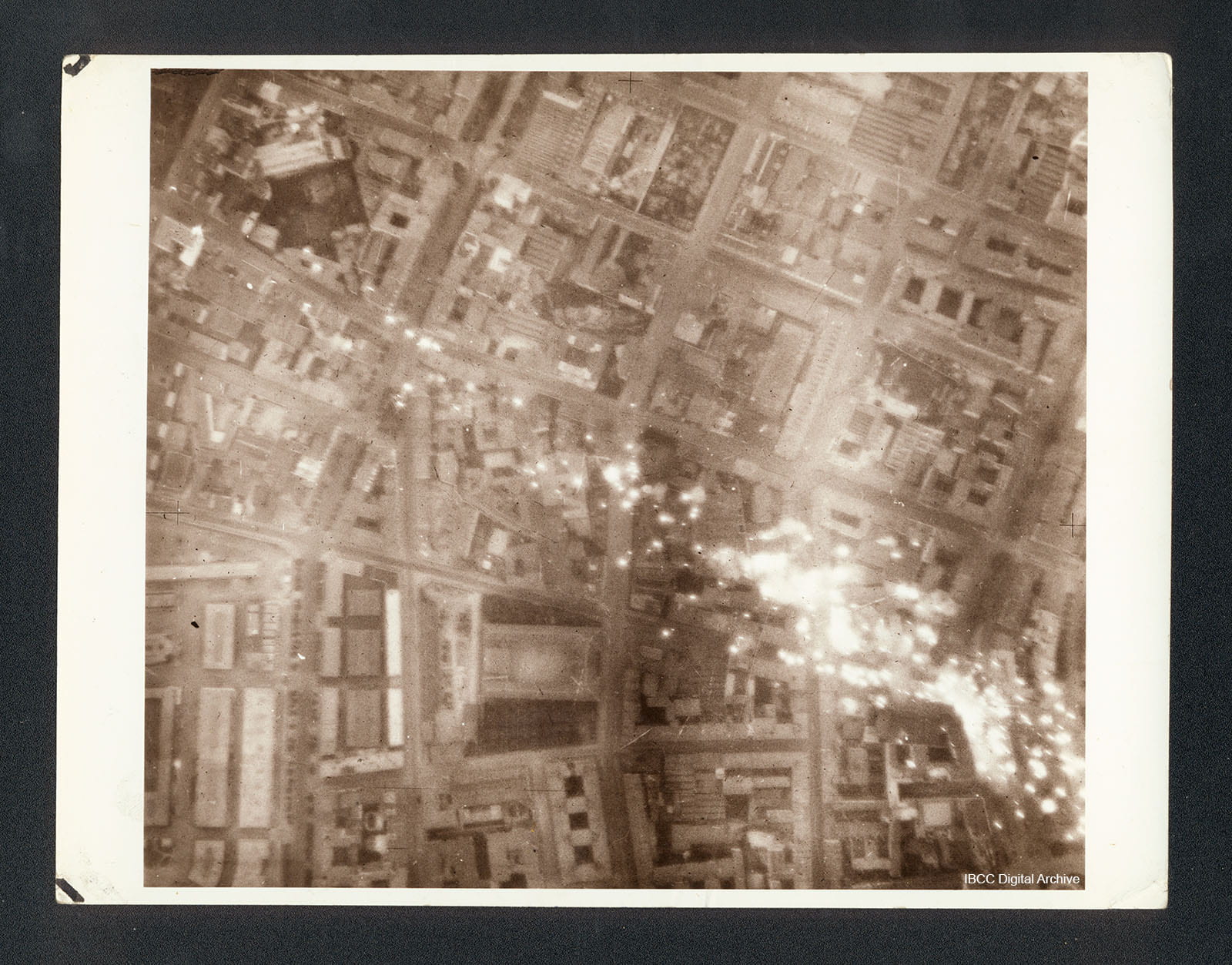

In can be argued that bombing warfare in Milan was predominantly aimed at gaining political advantage by using overwhelming air power and display of force in order to destroy morale and shatter will to fight. “That was a terror raid” commented Harry Irons reminiscing the 24th October 1942 daylight bombing, which concentrated mainly on working-class neighbourhoods and civilian housing, and only secondarily on military targets.[5]

Daylight raid 24th October 1942. Incendiaries falling down on a crowded residential area between Piazza 5 Giornate and the central fresh food market.

“We went through the Alps, and this is what I call a terror raid” Harry Irons reminiscing the 24th October 1942 Daylight raid.This aspect of the war entered dramatically and overwhelmingly in the daily lives of people, emphasizing a sense of collective trauma of the people living in Milan. This can be only marginally captured by official documents and the stories based on these sources – conversely, it can be potently felt by stepping inside the shelter and allowing to be transported by emotions.

What EUMM has been trying to do for years with the aid of the permanent exhibition is to allow visitors to re-live the experience of being at the receiving end of the bombing war, as endured by women and men at the time. In doing so, it creates a shared memory space. The Breda shelter, once framed in this way, does not only represent a place to be looked after and preserved as a relic of a past that is no more. On the contrary, it transforms itself into a memory object able to ‘make the past speak’ and brings it back to the present days.

This has been made possible by different choices. On the one hand, by leaving the space in its original condition: dark and cold, with uncomfortable wooden benches, and the claustrophobia given by a confined space. On the other hand, by recreating some immaterial elements of the past: digital video, or bombing sounds that accompany the visitor’s descent into the shelter. In this way, memory becomes embedded into a material object and is transported into the present. This leaves the visitor with the feeling of having gone through what they just saw and heard. In a way, the war period is transposed into the present: the present intertwines with a past that seems to re-materialise now.

A further element is the synchronic and diachronic conversation that links place and individuals. Being confined in a dark and inhospitable space whilst hearing war sounds leads us to immediately empathize with those who went through such experiences. This applies to the workers that used the shelter, but also civilians who resorted to cellars or the few public raid shelters set up in Milan and elsewhere in Italy. At the same time, it compels us to engage synchronically with other fellow visitors. They were strangers until the feelings of anxiety, fear and unease kick in.

Another point of my research has been understanding the emotional impact that the shelter has on people. It is so powerful and immediate that it compels visitors to explore their feelings, coming to terms with them, and then discuss with friends and family members. They frequently come back – this process sustains footfall and broadened the scope of this memory preservation exercise.

My research has also involved other bodies operating in the area such as Sesto San Giovanni municipality, the district in which most of the Breda factory was situated. The intent was to understand how a public institution fulfills its responsibility of conserving and perpetuating the memory of the city.

What emerged was the constant dedication to engage with the younger generations by means of workshops and recreational activities. All this takes place within the ongoing process of having the city included in the Unesco World Heritage list in the category of evolving cultural landscape, a procedure which began in September 2010.

The similarities emerged between the Sesto Municipality and EUMM stem from their shared dedication to community engagements, as well as the multi-sensorial, hands-on experiences which were set up in different spaces. This is fostered by an open dialog among various local actors.

Lastly, my research drew on the life stories of eye-witnesses of the war who also visited the shelter in recent times.[6] Thanks to their testimonies, I understood how powerful Geertz’s paradigm is: the mind is never free and unspoiled but always shaped by the influence of the present time. This implies the re-construction and the re-elaboration of the testimonies. At the same time, this is a legacy worth preserving, especially in an epoch like ours which is rapidly approaching what scholar Mariann Hirsh, speaking about the Shoah, defined as «Postmemory». This a new phase of history in which all the direct witnesses have passed away, a condition which urges us to come to terms with our capacity to conserve and transmit to future generations the historical memory that has not t been experienced.[7]

My research left some questions open. For instance, what will happen to the district of Sesto (and its material and immaterial cultural heritage) if the UNESCO candidature is rejected? What will happen to EUMM if no longer supported by a public sponsor willing to increase its financial contribution as to sustain EUMM’s development?

These concerns are rooted in the fact that Milan is an outlier when compared with other mayor Italian cities. Being Italy’s financial capital and economic powerhouse, it does not look back to the past but steams full throttle into the future: an ever-evolving skyline, new branches of the underground mass transport system, the endless redevelopment of old neighbourhoods. The list goes on and on.

I subscribe the view that the crux will be ‘how’ this memory will be preserved.

The shared commitment to collective integration and a strong local presence are – in my eyes – the best and most effective way of conserving and transmitting heritage to future generations. The museum, with its emphasis on the practical and sensorial aspect of knowledge, will also play a crucial role.

Partial answers to these questions my come from a broader debate, in Italy and in other countries, regarding heritage landmarks. This should involve local institutions and other stakeholder in a broad-scope discussion.

Federica Lampugnani

Acknowledgments

I am especially grateful to my supervisor, Professor Ivan Bargna, as well as to Alessandra Micoli and Michela Bresciani (both at EUMM) for their constant support and for trusting my research skills. Their help was decisive for me, not only in terms of practical support but above all for its human dimension.

Finally, a heartfelt thanks goes to those who have entrusted to me their war time stories, in particular Inge Rassmussen and Giuseppe Pirovano. They were generous with their recollections, which are especially valuable for the emotional and the historic value.

Notes

[1] Speech by Liliana Segre during the event organised for Holocaust Day at the Arcimboldi theatre on January 15th 2019.

[2] Federica Lampugnani, ‘Il Giorno della Memoria. La commemorazione della Shoah in Italia. -The day of memory. The commemoration of the Holocaust in Italy’. University of Milan, 2014-2015.

[3] Geertz Clifford, The interpretation of cultures, First edition, 1973.

[4] Bourdieu Pierre, Esquisse d’une théorie de la pratique, Droz, Genève, 1972; Outline of a Theory of Practice, An invitation to reflexive sociology, Bollati Boringhieri, 1992.

Csordas Thomas, Embodiment and experience. The existential round of culture and self, 1994.

[5] Parisi Sebastiano, Milano sotto le bombe (Raids on Milan), for the first time all the reports of the Allied forces bombings, Macchione, 2017.

[6] I’m referring myself, in particular, to Milena Bracesco, Inge Rassmussen and Giuseppe Pirovano. Milena is the daughter of Enrico Bracesco, a worker in Breda’s fifth aeronautical section, deported in working camps after the strikes in March ’43 and ’44. When Milena’s father died she was a year and a half old but she tirelessly worked all her life to piece together the story of her family. Inge and Giuseppe, instead, went through the bombings in Milan since, at that time, they were attending secondary school there. The interviews to Inge and Giuseppe have been recorded on the 5th and the 6th of December 2018.

See Federica Lampugnani, EUMM e il bunker Breda. La patrimonializzazione della memoria storica nel Nord Milano, University of Milano-Bicocca, 2019, page 100 to 118.

[7] Hirsch Marianne, Material Memory: Holocaust Testimony in Post-Holocaust Art in Shelley Hornstein, Jacobowitz Florence (edited by), Image and remembrance: representation and the Holocaust, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indianapolis, 2003, page 115.