As promised in my previous blog about Leipzig, here are some thoughts on the way the Nuremberg operation is remembered. Although not as well-known as the Dams raid or Dresden, the events on the last night of March 1944 have played a role in framing the way Bomber Command is remembered. On that one night, 95 aircraft were lost, and 545 airmen were killed. In this post I consider the Nuremberg raid in the historiography, through intertextual references, and in the IBCC Digital Archive’s oral histories.

It was argued during the planning stages, that the operation should have been scrubbed. There were conflicting weather predictions, the half-moon was up, and the route included a straight leg of 260 miles. On the night, Luftwaffe night fighters assembled at two beacons along the route. Spoof raids did not fool them and the combination of the moonlight above a cloud layer, the formation of contrails and the addition of fighter flares made Halifaxes and Lancasters easy to spot. Jeff Gray was a pilot with 61 Squadron; interviewed by David Kavanagh in 2015, he remembered:

“the weather forecast was completely the opposite… it was clear all the way except the target was cloudy and so I think the actual attack on the target was not very clever, but in a way it helped the end of an era. They switched us to the French targets.”[1]

Nuremberg was the last operation of what Arthur Harris called the Battle of Berlin. From April 1944, Bomber Command’s efforts were focussed on preparation for the D-Day offensive. Although it was not known at the time, Nuremberg was Bomber Command’s greatest loss of the war. The British press reported the numbers of missing aircraft but claimed that the RAF fought their way to the target and destroyed it.[2] However, the attack was scattered and less than 100 people were killed by the bombing.

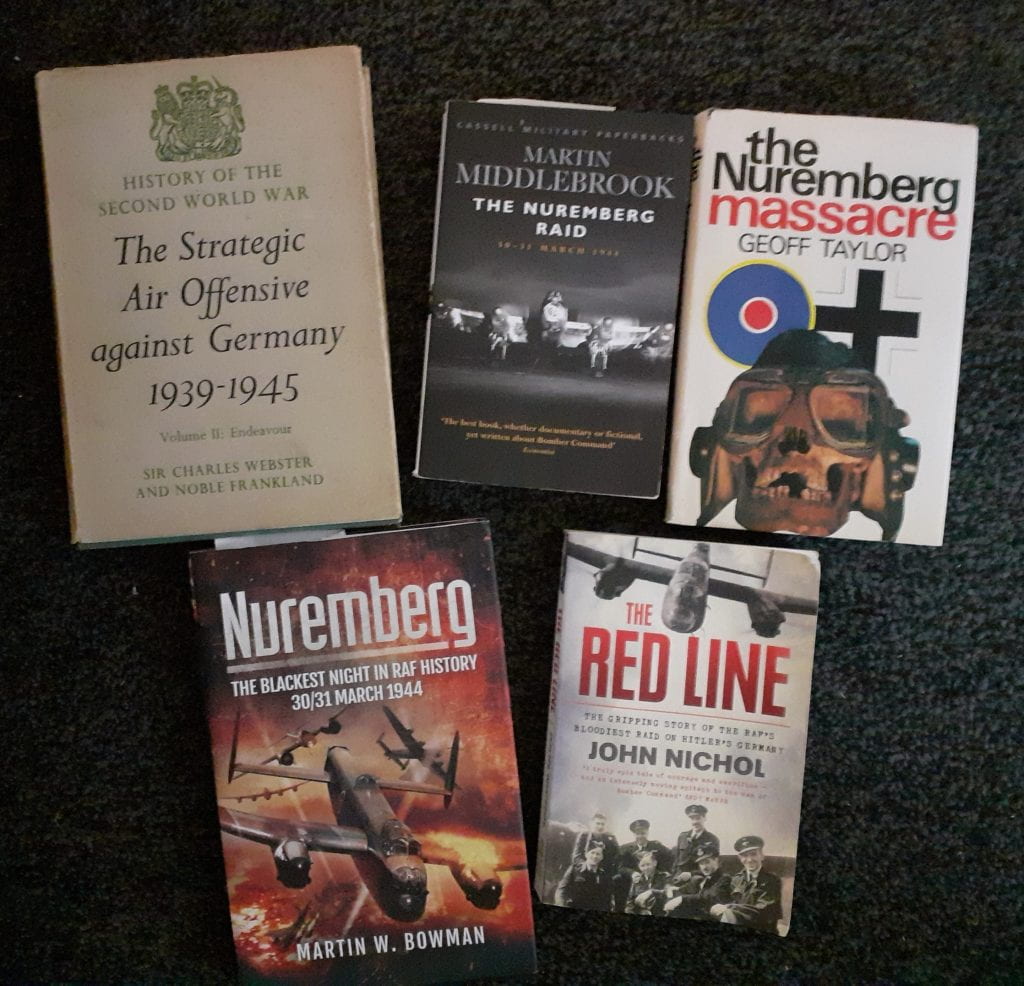

Some of the historiography.

Go to texts about the disastrous Nuremberg operation include Martin Middlebrook’s The Nuremberg Raid (1973), Geoff Taylor’s The Nuremberg Massacre (1980) and John Nichol’s The Red Line (2014). Middlebrook, is pretty much the definitive history. Taylor was a pilot on 207 Squadron and was a POW at the time of the raid, and his book is probably at its best when he is discussing his own experiences. John Nichol admits that he tried to write a best seller based on oral history.[3] The operation was retold in the late 1970s; for children by Andrew Davies in Conrad’s War (1978) and by Peter Durrant’s BBC2 TV play The Brylcreem Boys (1979.) Both have been influential in the cultural memory of the raid, but every retelling of Nuremberg refers to Martin Middlebrook’s work. For example, Middlebrook tells the story of Tom Fogarty DFM, a pilot with 115 Squadron. His Lancaster Mk 2 was damaged and went into a shallow dive near Stuttgart. The crew decided to bale out but when the flight engineer could not find his parachute, Fogarty gave him his. The crew survived and were joined later by their pilot in captivity.

“At 500 feet he had put down full flap, switched on his landing lights, found a convenient field and set his Lancaster down on its belly. Fogarty… came to lying in the snow surrounded by farm workers.”[4]

In Conrad’s War, Conrad gives his parachute to Towser, his dog, and crash lands his Airfix model Lancaster in the snow.[5]

The cover of Conrad’s War by Andrew Davies

Andrew Davies included several Bomber Command tropes in Conrad’s experience of the Nuremberg operation. Suggesting a Lack of Moral Fibre, one airman drops his pipe which “shattered into little bits”. He exclaimed “I’m not going, I’m not going anymore, I can’t go, it’s not fair anyway, they know I’ve got asthma.”[6] Later, Conrad thinks of the Luftwaffe night fighters:

“Conrad suddenly recalled the shooting booth at the fair. A long row of battered metal ducks flew with the speed and panache of a snail’s funeral from left to right across a black background. You lined up your gun, and waited for one to cross your sights. There was plenty of time to squeeze the trigger slowly… That’s what they would look like to the Messerschmitts, Conrad thought. The ducks would clang over backwards and disappear from view. He didn’t want to clang over backwards and disappear from view.”[7]

Later, Conrad considers the consequences of what he had done by bombing Nuremberg; “had one of his bombs gone through someone’s gran’s roof?”[8]

Based on the relationship between himself and his son,[9] Davies considers the war from multiple perspectives; people from both sides, military and civilian, are involved in the story. Rather than heroically glorifying escape, personnel in Colditz are content to wait for the war to end, and the horrors of war are portrayed in a scene with an ambulance full “of wounded and dead people, men, women and children.”[10] In this way Conrad’s War gives a nod towards Len Deighton’s Bomber (1970) but in the briefing chapter, and by choosing Nuremberg as the target, it also conforms to the narrative of aircrew as victims.

Screen grab from The Brylcreem Boys.

Starring Timothy Spall and David Threlfall, the play was shown on BBC 2 in 1979 and repeated in 1981. Set in a ward in ‘Peacehaven hospital,’ six neuropsychiatric aircrew patients re-enact their last operation with the help of a frost-bitten Erk who takes on the role of their wireless operator. Once again, their target is Nuremberg. All are medical cases, but reviews and notes in the script incorrectly discuss the play in terms of LMF and PTSD.

The bombed are invisible throughout the play, and the Lancaster crew are portrayed as victims. Once in the ‘air’, just about everything that could go wrong does go wrong. They deal with fighters, flak, vapour trails, H2S on the blink, strong winds, crew members being wounded, and Scarecrows. When they reported seeing a four-engine bomber explode in mid-air aircrew were informed that they had actually seen a ‘Scarecrow’, a pyrotechnic designed to replicate a bomber exploding as a deterrent. The fictitious crew of S-Sugar argue whether the blinding flash they witnessed was a Scarecrow or not. Bruce, the flight engineer in The Brylcreem Boys exclaims, “Scarecrows be buggered. That was that Lanc exploding. He got a direct hit.”[11]

A “Scarecrow” exploding, The Daily Express, 15 April 1944

In the late 1970s, Geoff Taylor and the veterans he contacted while researching The Nuremberg Massacre were all convinced by the Scarecrow myth.[12] However, over 40 years later, most veterans who mentioned Scarecrows in interviews recorded for the IBCC Digital Archive were aware that the Germans had no such weapon.

Rusty Waughman was a pilot on 101 Squadron. His squadron lost seven Lancasters on the Nuremberg operation. He remembered that “the Nuremberg raid left the biggest scar… mental scars w[ere] far, far greater than the physical scar and that really… sunk home when you realise what the attrition rate was.” However, he also added detail that must have originated from post war sources quoting “there were more aircrew killed on that one night than there was in the whole of… the Battle of Britain.”[13]

Like any other source, veteran interviews need to be used carefully. As Bomber Command navigator and historian, Noble Frankland pointed out, memory is unreliable.[14] In the same way that in Conrad’s War, Davies embellished on Middlebrook’s description of Fogarty’s crash landing, interviewees use external sources to inform their testimonies. John Nichol agrees that veterans add detail, context, and facts they have accumulated from books, TV and film to their narratives.[15] Aired in the days with only three TV channels and huge viewing figures, many veterans will have watched The Brylcreem Boys or read books that point out the Scarecrow myth. They were also influenced by the context at the time their memories were recorded. The history of Bomber Command is contested and is difficult heritage. It is sometimes reduced to the binary of the Dams or Dresden. The operation to attack the dams of the Ruhr is remembered as a heroic sacrifice, while the firestorm of Dresden in 1945 is used to highlight the controversies surrounding strategic bombing. When Nuremberg is remembered, aircrew suffering and loss is often used to highlight the futility of war and to counter accusations about Dresden. As part of these narratives, tales of LMF, Scarecrows and other details used in cultural retellings, like The Brylcreem Boys, are both effective and popular. Sadly, Martin Middlebrook died recently, but I’m convinced that all new interpretations and histories of the Nuremberg operation will continue to be influenced by his work.

References

Bowman, M (2016) Nuremberg: The Blackest Night in RAF History

Davies, A (1978) Conrad’s War

Deighton, L (1970) Bomber

Durrant. P (1979) The Brylcreem Boys

Frankland, N (1998) History at War

Iredale, W (2021) The Pathfinders

Isaacs, J The World at War (1973) Episode 12, “Whirlwind: Bombing Germany (September 1939 – April 1944)”

Middlebrook, M (1973) The Nuremberg Raid

Middlebrook, M and Everitt, C, (1985) The Bomber Command War Diaries

Nichol, J (2014) The Red Line

Taylor, G (1980) The Nuremberg Massacre

[1] David Kavanagh, “Interview with Jeff Gray,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed March 25, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/3411

[2] The Times, Saturday, Apr. 1, 1944, p. 5

[3] Conversation with John Nichol, 2023

[4] Middlebrook, M (1973) The Nuremberg Raid, p. 229

[5] Davies, A (1978) Conrad’s War, pp. 70-71. See also Nichol, J (2014) The Red Line

[6] Davies, A (1978) Conrad’s War, p. 49

[7] Davies, A (1978) Conrad’s War, pp. 60-61

[8] Davies, A (1978) Conrad’s War, p. 67

[9] Conversation with Andrew Davies, 2023

[10] Davies, A (1978) Conrad’s War, p. 126

[11] Durrant, P (1979) The Brylcreem Boys, p. 40

[12] Taylor, G (1980) The Nuremberg Massacre, p. 26. “Scarecrows were a product of the ingenious minds of the German psychological warfare specialists – they were flak shells which, on bursting simulated an exploding British bomber complete with blazing, dripping petroleum, flares and signal cartridges. The effect was enough to startle and dismay inexperienced crew.”

[13] Chris Brockbank, “Interview with Rusty Waughman. Two,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed March 25, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/3517

[14] Frankland, N (1998) History at War, p. 34

[15] Conversation with John Nichol, 2023