Even a desultory walk in the most inconspicuous Italian town shows a clear imbalance in the memorialisation of the Second World War. Leading resistance figures, victims of reprisals, and key events of the partisan struggle are widely represented: piazza resistenza partigiana, via martiri della Resistenza, corso XXV aprile and piazza Sandro Pertini are recurring features of any urban landscape from Sicily to the Alps. On the other hand, the bombing war left fainter and less obvious marks on Italian toponymy. Traces are few and far between.

This bias is even more evident when figures are taken into account. The killing of all the Cervi brothers – seven communist activists who took active part in the Resistance – is remembered by street names all around Italy. Conversely, even bombings which caused a death toll in the region of hundreds of civilians have rarely memorialised in this way (if memorialised at all). Some notable exceptions are Piazza dei piccoli Martiri and Piazza Caduti sei luglio 1944, both in Milan. The former also stands out for the almost unique word choice of “martyrs” as a synonym for bombing victims.

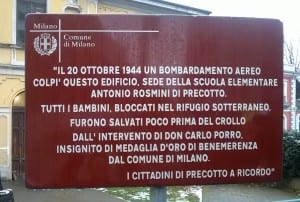

Another way the Second World War has been remembered is by small monuments and memorial plaques sponsored by local administrations or groups. They come in every shape and size, but a recurring feature is the elusiveness of the inscriptions: expressions such as “victims of enemy aircraft” or “killed by enemy action” are commonplace. Others resort to even more nebulous and essentially tautological expressions such as “victims chosen by Death”. In this case, invoking an impersonal force also resonates with style conventions of memorials erected to victims of natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, landslides etc. Not surprisingly, some local authorities took a step further and sanitised text completely by omitting any reference to human agency. The following example (viale Monza 233, Milan) is illuminating:

Sign translates as follows: “On 20 October 1944 an aerial bombing hit this building, which at that time housed the “Antonio Rosmini” primary school. All children trapped inside the underground shelter were rescued just before the collapse by vicar Claudio Porro, recipient of the civic merit medal awarded by the Milan City Council. The citizens of Precotto.”

The sign has all the hallmarks of a compelling story. The initial order is threatened by an evil power; innocents are defenceless. The hero steps in, leads the forces of good, saves the day and obtains his well-earned reward. The most interesting bit is the information omitted: who dropped the bombs on a Milan residential neighbourhood (the United States Army Air Force); why (a controversial navigation blunder) and finally the context, as this rescue is just an episode of the highly contentious 20th October 1944 Milan bombing. That day, a direct hit on the nearby “Francesco Crispi” primary school caused the death of 184 children wiping out an entire generation. The Piccoli Martiri mentioned above.

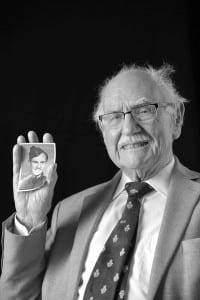

The International Bomber Command Centre Digital Archive managed to interview Paolo Bottani, one of the very survivors rescued by Carlo Porro.

The interview was conducted by Erica Picco (Laboratorio Lapsus) on 2 December 2016.

“The moment the siren went off, we children were rounded up and our teachers hastily shepherded us down into the shelter. We were in high spirits, none of us realised that we were about to be bombed. We cheered because our class had been disrupted. Yeah, that’s true happiness! In the shelter we had good time: horseplay, you know, what children do. After a while, point black, the lights went out. Gosh! What’s going on? Then a terrible rumble came, the building shook and trembled, and rubble fell on me. Smell of dust and sulphur. Some children were crying, others moaning, one was covered in blood. At that point we realised how serious the situation was. I retained my composure nonetheless. I’m honest in saying that: I was fairly calm. Oh, yes, afraid but calm. After about ten minutes Father Carlo Porro assembled a rescue party of three or four volunteers, realised that we were trapped below and opened a small passage through which we were rescued. I was the penultimate to leave. The teachers remained calm and collected and managed to keep us in control. They formed a queue, pushed us up through a slope of rubble, so we reached the ceiling and someone from outside pulled us up, as if we were salamis [cured sausages were traditionally stored hanged]. The familiar urban landscape had changed beyond recognition. […] No living souls around, only deserted streets covered with rubble. I was walking alone covered in dust when I saw a derailed tram out of the tracks, and a bleeding horse without a hoof, moaning pitifully.”

Paolo was later celebrated as a star:

“I went back to Crema. The headmaster, the teachers, all Fascist propaganda so to speak, welcomed me almost as a war hero. I was held up as an exemplar figure, someone who did something praiseworthy, a deed inspired by a noble sense of duty. “The Allied bombings”, “American killers” they said – the usual propaganda. I was turned into a star and never had the opportunity to speak with my friends.”

In reflecting on his experience, Paolo Bottani makes his stance clear in no uncertain terms:

“I loathe war, any kind of war. I simply cannot grasp the sense of waging war. Since then I’ve come to understand that war is useless, really useless. How many friends of mine died while still in their childhood? How many fathers died on the front? How many mothers died among hunger and sufferings? What has war left? War is pointless […] All these events are etched in my memory – I’ve always been an avowed pacifist.”

A snippet of the interview with him has been translated in English and featured at the International Bomber Command Centre in Lincoln. Paolo Bottani passed away in Spring 2018, only a couple of months before his interview went live.

Alessandro Pesaro, Digital Archive Developer

I’d like to record my indebtedness to Sara Zanisi, research officer, Fondazione ISEC, Milan for revising the first draft of this post.

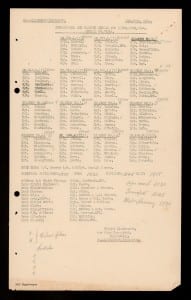

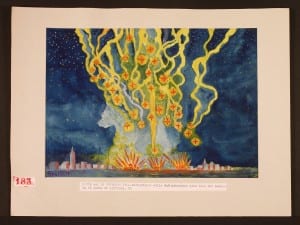

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010001](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010001-300x250.jpg)

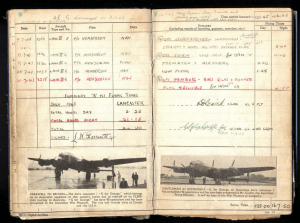

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010002](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010002-199x300.jpg)

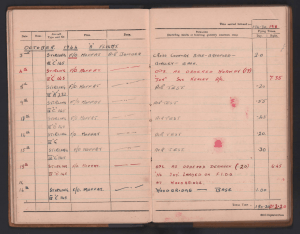

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010003](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010003-201x300.jpg)