Maintaining the clarity of our distinctive IBCC narrative voice has not been without its challenges within the partnership tasked with delivering the entire, ambitious project. Tensions in perspective have mostly been turned to highly creative use. Every now and then, however, challenges have been thrown up that have threatened to disrupt a singular voice.

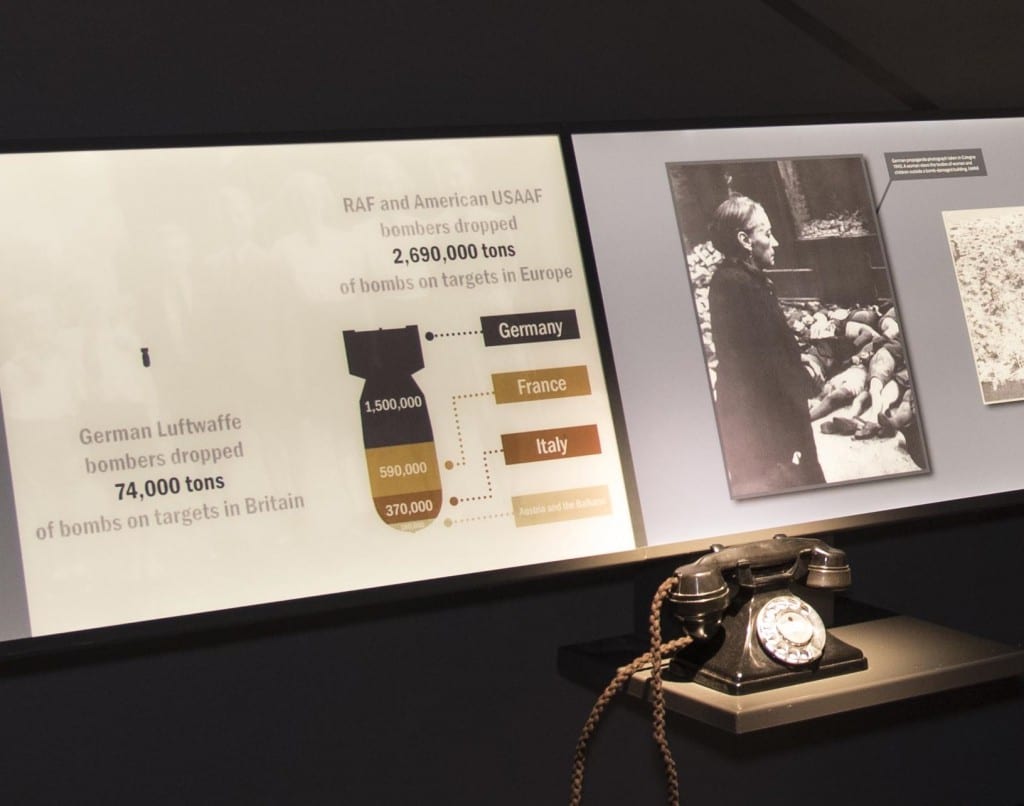

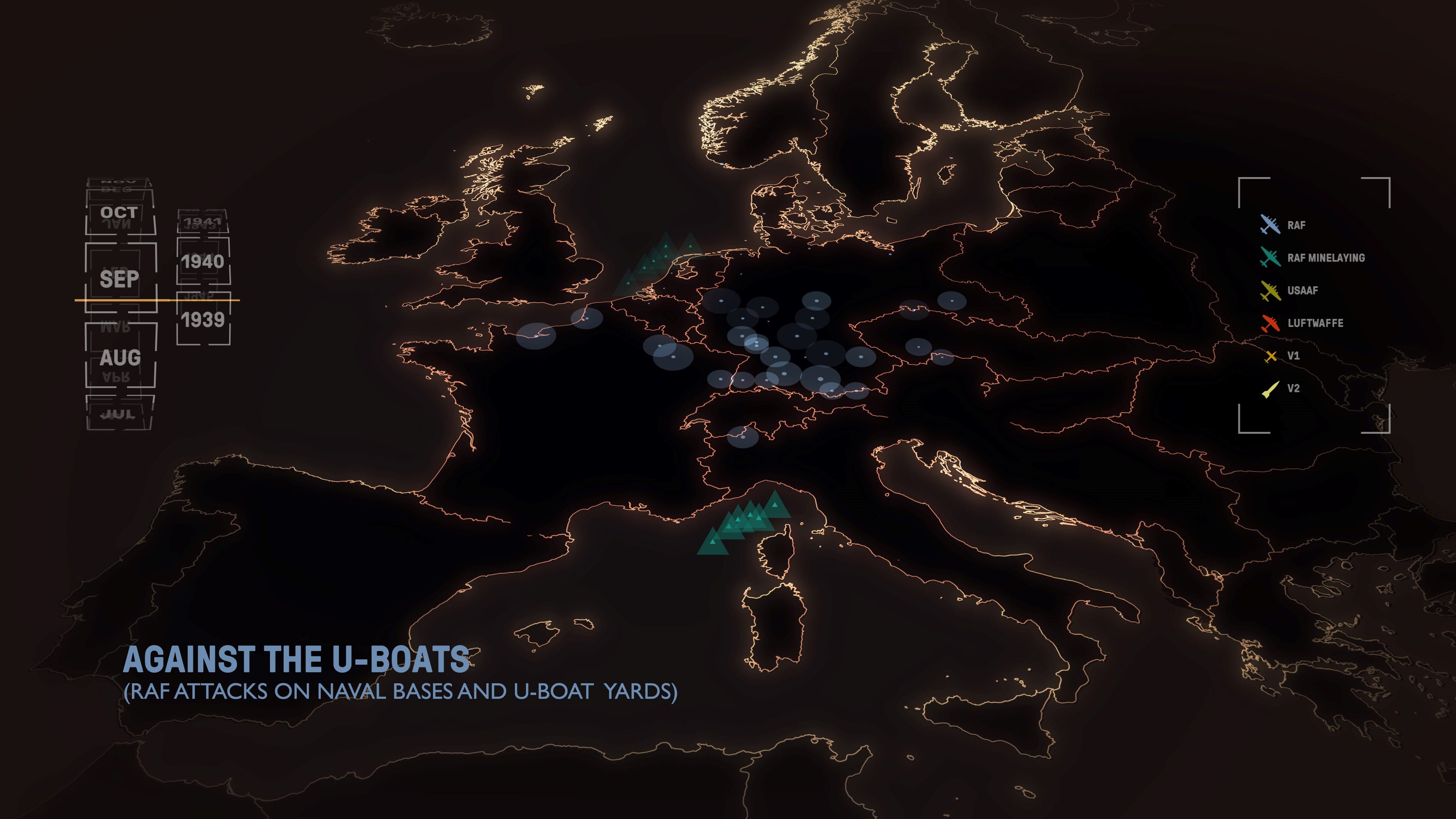

For example, our external partner decided to name the visitor centre the Chadwick Centre, after the designer of the Lancaster bomber. This seemed from our perspective in the partnership to be rather too ‘top down’, to focus too heavily on hardware not people, and to be too Lincolnshire-specific. (There are faultlines in the Bomber Command memorialisation community, split along bomber Groups and aircraft flown.) Out of respect we worked with it. We had interviewed Roy Chadwick’s daughter for the archive and she is included in the exhibition, speaking of her father. We included stories and images of crews who flew a variety of aircraft, and made efforts at wide geographical coverage. We were also mindful that all Bomber Command aircraft meant only one thing to those on the ground in occupied Europe: death and destruction.[1]

And now, on the eve of opening, the tone of our narrative voice has been altered by additions to the entrance area of the Chadwick Centre, without involving the exhibition/archive team. It is important to this explanation to note that the only area of the site that is behind a paywall is the exhibition itself. All other areas can be freely accessed. One anticipates that many more visitors will move through the ‘free’ than the ‘paid’ spaces.

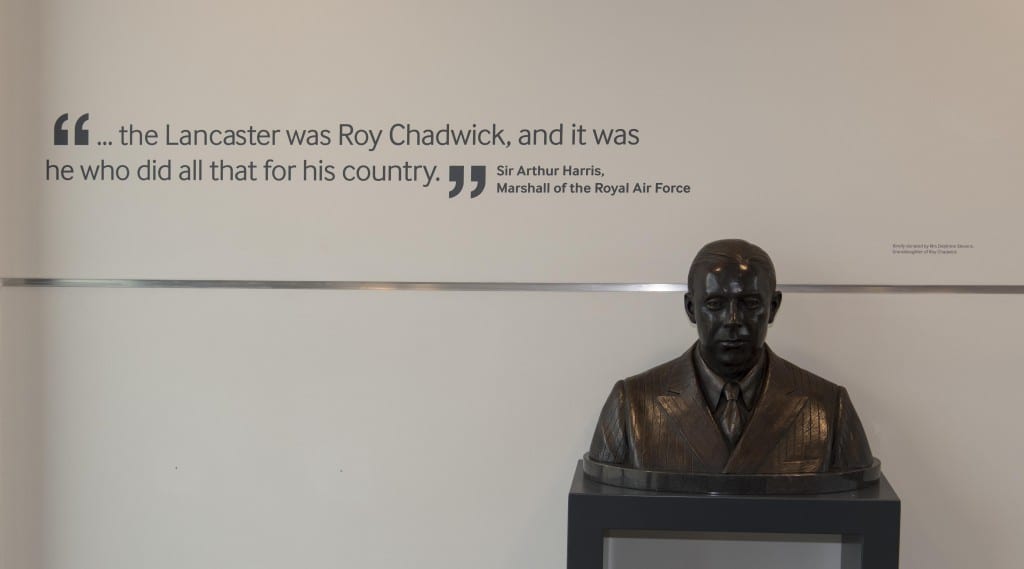

As one walks into the Chadwick Centre, one is greeted by a large quote on the wall by Arthur Harris, not only chief of Bomber Command but even today considered one of the most controversial figures in the Allied military command structure. Even (or especially) veterans and their families remain divided over his role and legacy, as testified in many of the interviews we have collected. Here, immediately, is a provocation, a call to an official victor narrative. The quote is about Roy Chadwick, a bust of whom (donated by his family) is positioned below it.

The bust of Roy Chadwick and the quote by Harris.

In another area of the entrance – harder to see until one is leaving – is the fifth verse of Laurence Binyon’s poem, For the Fallen.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again; They sit no more at familiar tables of home; They have no lot in our labour of the day-time; They sleep beyond England’s foam

It was written in 1914, a few weeks into the First World War. The fourth verse, beginning ‘They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old’, is now commonly associated with British remembrance and the poppy.[2] In the verse quoted, it is of interest that Binyon refers to ‘England’, not even Britain, nor its allies, so a contested issue within the victor narrative is introduced, compounding the implications for our wider interpretive scheme.

The overall impression now created in the entrance area is that the IBCC has not moved beyond a rather outworn, binary us/them perspective on the bombing war. (The decorative scheme in the café does nothing to disrupt such an impression, but that may be extending our argument too far.)

Another potential challenge is the ‘Knight of the Skies’. In October 2017, this sculpture was donated to the IBCC by a family with close connections to Bomber Command and who have lent significant support to the IBCC. The knight was one of 36 sponsored sculptures in Lincoln city centre’s Knights’ Trail over the previous summer.[3] Each sculpture was distinctively themed and painted by a different artist. The ‘Knight of the Skies’ wears flying gear and holds the IBCC spire as a sword above Lincoln cathedral and fields of poppies. On its side, a Lancaster and its crew stand beneath a shield bearing the Bomber Command motto, ‘STRIKE HARD STRIKE SURE’. The last British survivor of the Dams Raids, Johnny Johnson, has autographed the knight. It represents a heroic view of those who flew in RAF Bomber Command.

The Knight of the Skies

The knight has been displayed in the Remembering Bomber Command gallery, which is entirely appropriate. This is, after all, one local form of remembering that contains multiple personal stories, not only connected to the war but to the IBCC.

At issue for the interpretation is its current location, presiding over the entrance area as visitors approach from the carpark. If one does not intend viewing the exhibition, it is the only bit of the exhibition one gets for free.

What we have for the opening of this prestigious new development in Lincoln, then, is not one but two voices that sit awkwardly side by side, a reminder of the heritage dissonance that has long been identified as one of the dangers of mobilising an unruly past for contemporary purposes, such as commemoration and place-making.[4] We wish it were not so and that the quotes at least could be replaced. We have concerns about how the Centre may be portrayed online and how that may shape the decision to visit (or not) among those who are not our natural/predicted audience – although we want them to be impressed, too.

This reflection sums up our views as we let go of our interpretive work at the Centre and give over to visitors to interact with the interpretation, create their own experiences and take away their own memories.

Dan Ellin, Heather Hughes and Alessandro Pesaro

[1] In recent years there have been a number of landmark studies on this theme, offering very different perspectives to those produced in the Cold War context. See for example Richard Overy, The Bombing War, Europe 1939-1945. Allen Lane, London, 2013; Dietmar Süss, Death From the Skies: How the British and Germans Survived Bombing in World War II, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014; Jörg Friedrich, The Fire: The Bombing of Germany 1940-1945. Columbia University Press, New York, 2006.

[2] For the issues associated with poppy remembrance, see Maggie Andrews, ‘Poppies, Tommies and remembrance: commemoration is always contested’. In Soundings, Vol. 58, 2014, pp 98-109.

[3] http://www.knightstrail.com/ accessed 31.12.2017.

[4] See J. E. Tunbridge and G. J. Ashworth, Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. John Wiley, Chichester, 1996.