The docufilm explores the difficult legacy of the United States Army Air Forces bombing of Sant Ilario (13 September 1944), in which 18 inhabitants of a small community in the Trento province lost their lives. Numbers may pale in comparison to other strategic bombings on the European theatre but the aim is rather to explore the impact of a dramatic event on small, close-knit community which was largely unprepared to cope with it, and to explore its difficult memorialisation.

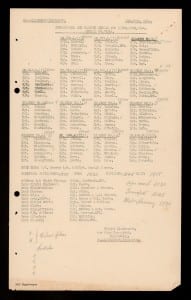

Sant Ilario bombing victims. Photo courtesy of Maurizio Panizza

Researched and presented by Maurizio Panizza and filmed by Federico Maraner, the documentary brings together an orchestra of voices with different perspectives on the event. Commentary is minimal, mostly intended to provided background; the documentary avoids facile effects and the overall tone remains sombre and pensive throughout. No overt judgements are given and those who were at the receiving ends of the bombing war speak as eyewitnesses, not as judges; they remember, not accuse.

The script uses plain language without indulging in aerial warfare technicalities: the life histories of the informants are thrown in sharp relief without rhetoric. Minor details are used to convey a potent sense of reality, for example the overwhelming smell of dust and explosives, or the eerie silence after the bombs went off. Both are recurring elements in the stories of bombing survivors.

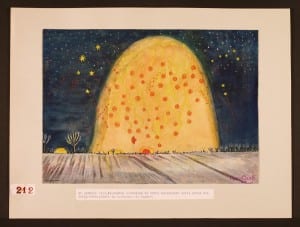

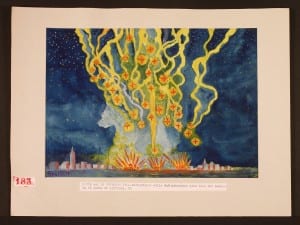

One of the most striking aspects of the event is that the Sant Ilario bombing was not even a bombing in the first place. Bombload was randomly jettisoned, the bombs fell on that specific spot by pure chance, and the casualties were mostly peasants who had little or no connection to the war effort. A provincial backwater removed from the main targets, the village was considered a safe heaven, its local population on the increase owing to an influx of evacuees. Destruction and death – admonishes the documentary – are not only blind but pointless: suffering had no apparent meaning. In this vein, even describing aircraft as “silvery birds” has a subtle logic. It captures its beauty and grace, but also stresses an inhuman, purely mechanical destructive power. It conveys a sense of wonder reported by quite a few witnesses of aerial warfare, but on the other hand suggesting an overwhelming force which leaves people on the ground defenceless. The random nature of suffering and death is made explicit by one poignant passage: evacuees who had having prior knowledge of bombings and try to warn others are killed; those who ignored their advice are spared.

Brione, the very spot where the bombs fell. Photo: courtesy of Maurizio Panizza

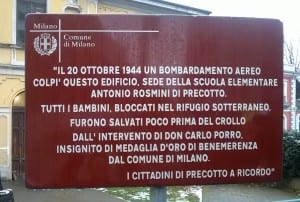

This unresolved duality is emphasised by a shrewd use of present-day footage, especially when the camera lingers on the gentle slopes of nearby hills, sleepy villages, and lush vegetation. Camera movements subtly suggest a sense of time, passage, and transformation but there’s a rather disturbing undercurrent. Has suffering been properly elaborated or is it still present? Did the passing of time heal the wounds or the events have merely fallen into oblivion, replaced my more pressing issues? Have we learned from the event? Those questions remain on the background when the documentary describes the difficult memorialisation of the bombing. Lacking recognition from authorities, local people took ownership of their own heritage by erecting a small memorial funded by subscriptions. It still stands, recognised as a focal point of the local community.

Come uccelli d’argento [like silvery birds]

by Maurizio Panizza and Federico Maraner

Italy, 2017, 30’ https://vimeo.com/296575801

Alessandro Pesaro, Digital Archive Developer

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010001](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010001-300x250.jpg)

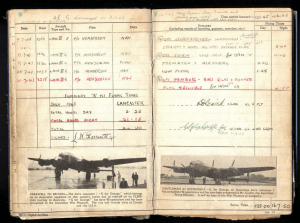

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010002](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010002-199x300.jpg)

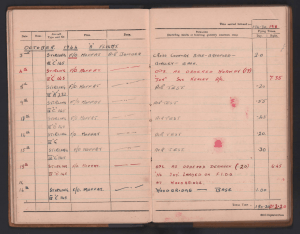

![E[Author]BeltonSLS400731-010003](https://ibccdigitalarchive.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2018/09/EAuthorBeltonSLS400731-010003-201x300.jpg)