When the Royal Air Force was established on 1 April 1918, Prime Minister David Lloyd George hailed South African statesman Jan Christiaan Smuts as its father.[1] With hindsight, there are several others who can claim such a mantle, most prominent among them its first Chief of Staff, Lord Trenchard.[2] Yet how Smuts came to be in this position, and how he promoted the use of air power, are both revealing of the role of Empire in the history of the RAF and of aerial bombing in the interwar period.

Smuts had won fame as a Boer commander in the South African War (1899-1902), employing guerrilla tactics that the British found exceedingly hard to deal with. In the post-war aftermath, he was one of those prepared to work with the British to repair Boer-British relations in South Africa. That reconciliation process was viewed at the time entirely in ‘white’ terms, even though this was never a ‘white man’s war’: South Africans of every community had been sucked into it, either directly or indirectly.[3] Relations were repaired sufficiently to bring into being the Union of South Africa in 1910, yet when world war broke out four years later, the extent of the continuing faultline was all too clear.

While most English-speaking settlers vigorously campaigned to support Britain, most Boer/Afrikaner nationalists believed South Africa should stay out of the conflict; diehards declared support for Germany. Louis Botha, the South African premier, and Smuts, as Minister of Defence as well as of Mines and Industry, took the country in on Britain’s side. Such was Boer hostility that Botha and Smuts had to put down a major rebellion and lead volunteer troops themselves in the invasion of German South West Africa. Botha took command of the northern sector and Smuts of the southern one; serving as a bugler under Smuts in the 1st Rhodesian Regiment was one Arthur Travers Harris.[4] The German governor surrendered within six months and Smuts worked hard to ensure that South Africa would have a hand in ruling the territory after the war.[5]

Jan Smuts. © IWM (HU 33933)

By 1917, he had acquired a reputation as a firm and effective commander of regular troops both in South West as well as in East Africa. Lloyd George invited him onto the war cabinet in July of that year and tasked him with sorting out the air defences of British cities and producing a report on the feasibility of a combined air force. Two separate air services had recently come into existence, but belonged to the navy and the army: the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps. Co-ordination between them was patchy at best.[6]

He achieved the first task, of producing a defensive plan for cities, very quickly. The second was more politically sensitive. As an outsider, republican yet pro-British, Lloyd George considered Smuts best placed to negotiate the turf wars between the army and navy over the future of air power. (He had earlier managed to broker talks between republicans and unionists in Ireland.[7]) He was already a convert to the military potential of aircraft. He had watched his first aerial display in Cape Town in 1911, when two visiting British aviators demonstrated their skills. This had led directly to the formation of the South African Aviation Corps in 1913.[8]

Smuts presented his report to the cabinet in August 1917. No time was to be lost; a new, unified, independent air force should be established as soon as was feasible. There were plenty of olive branches handed to the Admiralty and the War Office regarding transitional arrangements and staffing the new service.[9] The Smuts Report is interesting for its assumption that the recommended new service would not only play a primarily offensive function but also a decisive one. ‘The day may not be far off when aerial operations with their devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war’, Smuts declared. Also of interest is the extent to which Smuts’s grasp of both regular and irregular warfare led him to stress the ‘command and control’ mechanics of the new force. (The full report may be viewed on the RAF Museum’s website here and there is a transcript below.)

Thus was born the world’s first independent air force, although contests continued between it, the army and navy over the allocation of resources and the deployment of air power. The ending of hostilities in November 1918 further deepened uncertainty about the future of an independent RAF, as the military machine was trimmed back considerably.[10] Thousands of new aircraft were scrapped and many airfields returned to farmland.

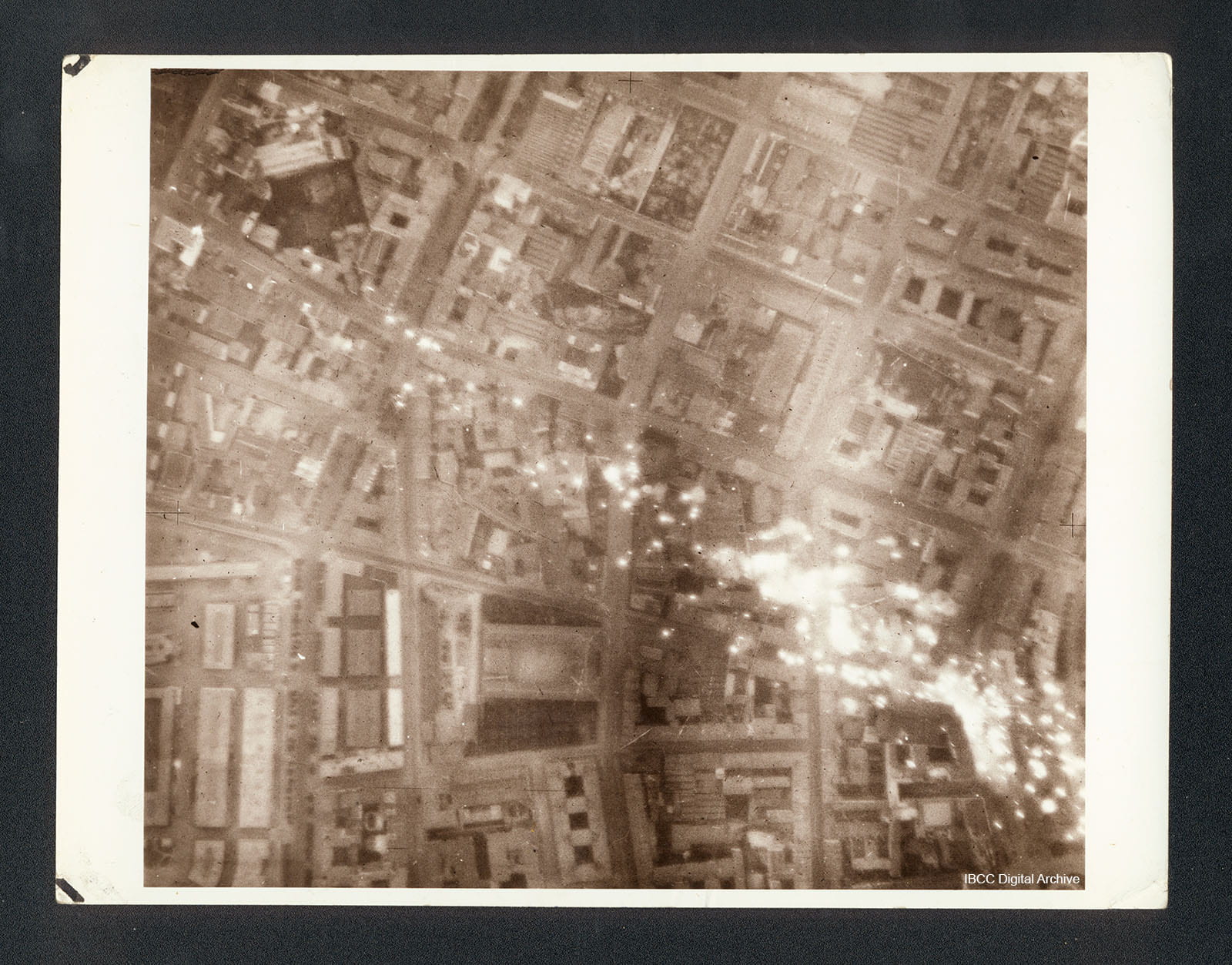

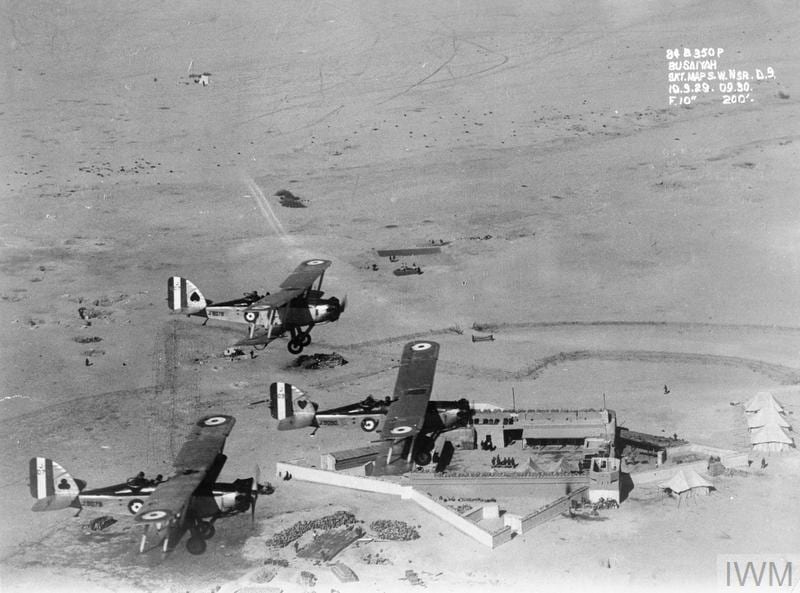

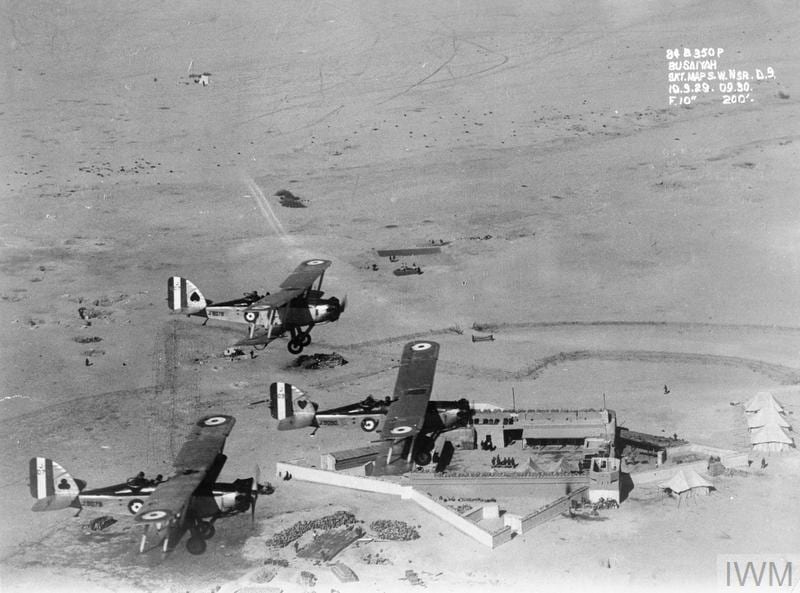

In many ways, the discovery of the advantages of air power to patrol empire, or air policing, helped the RAF to stabilise its role: ‘aviation promised to be the trump card, the perfect means of keeping colonial people on the straight and narrow path’.[11] It was thought to be a cost-effective means of bringing under Britain’s control all the ceded German and Ottoman territory,[12] as well as dealing with rebellious behaviour in its older possessions. In addition, as a British colonial official remarked of West Africa, ‘the terror caused by [aircraft] would probably do away with any need for bloodshed’.[13] One understands how traumatic the memories of trench warfare must have been but still, only British blood seemed to matter. It was also misleading to claim that ground troops could be completely dispensed with. Nevertheless, the dramatic impact of aerial bombing on the morale of ‘tribal peoples’ featured prominently in imperial thinking at the time.[14] Thus, with political support at Westminster, the RAF played an important role in interwar ‘pacification’ campaigns – Somaliland, Sudan, Persia, Mesopotamia and India, among others.

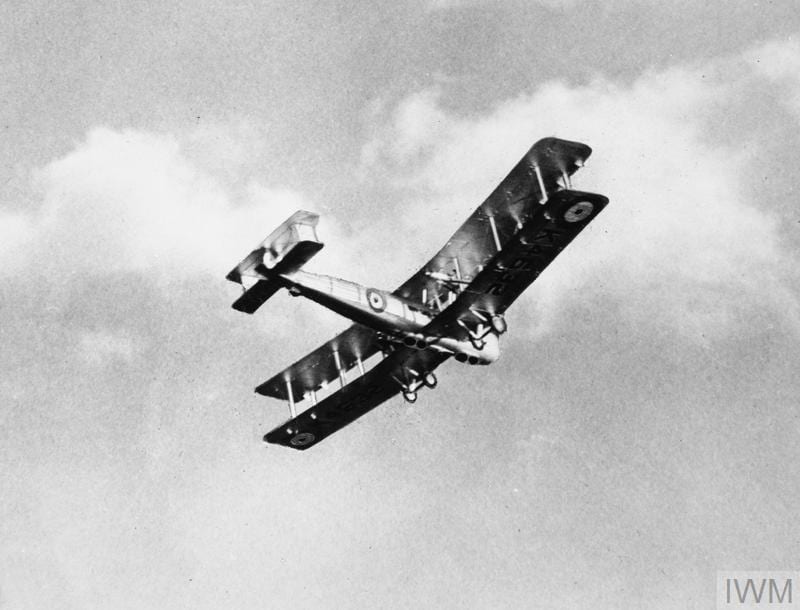

RAF 84 (Bomber) Squadron in Mesopotamia, 1928. © IWM (HU 33933)

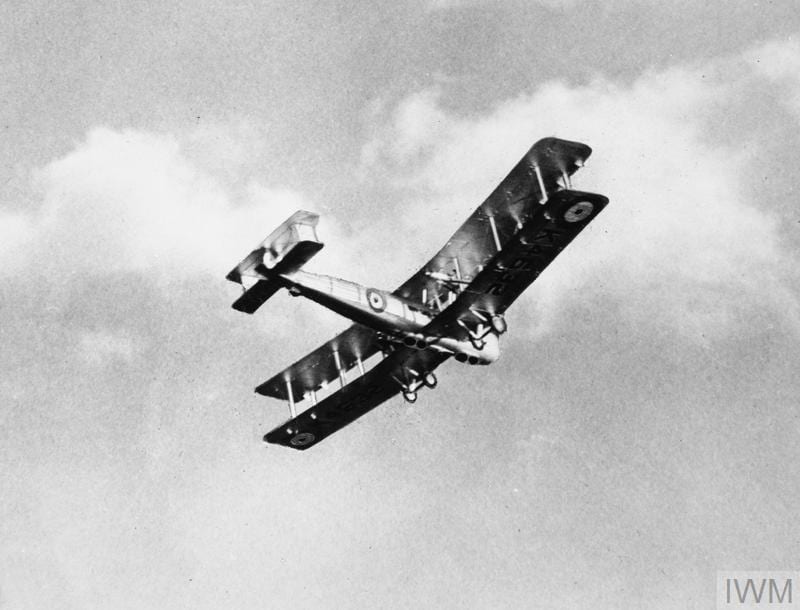

Harris, as it happens, was rising through the ranks of the RAF in the 1920s and 1930s as a result of his involvement in these air policing campaigns. He reported from Kenya in 1932 that, at the request of the native commissioner, ‘we flew over and bust-up a meeting of Nandi witch doctors with considerable success’.[15] At the time of the Palestinian revolt in the later 1930s, he declared that ‘one 250lb or 500lb bomb in each village that speaks out of turn’ would be decisive.[16] How those on the ground reacted to being bombed, or to that less violent means of intimidation, ‘sky shouting’, does not seem as yet to have been the subject of research.

A Vickers Valentia fitted with four external loudspeakers for ‘sky shouting’. © IWM (Q 73341)

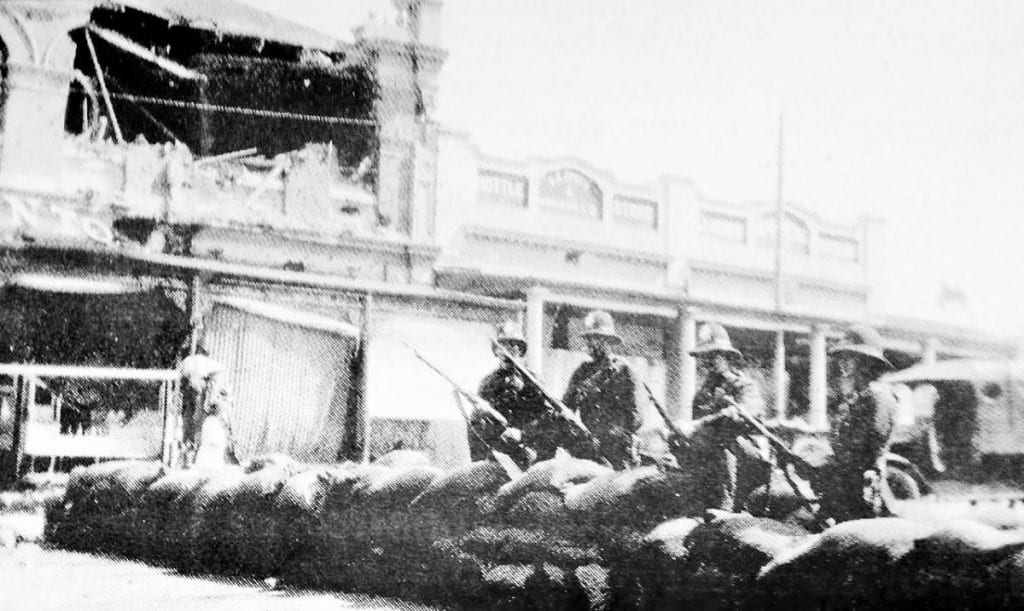

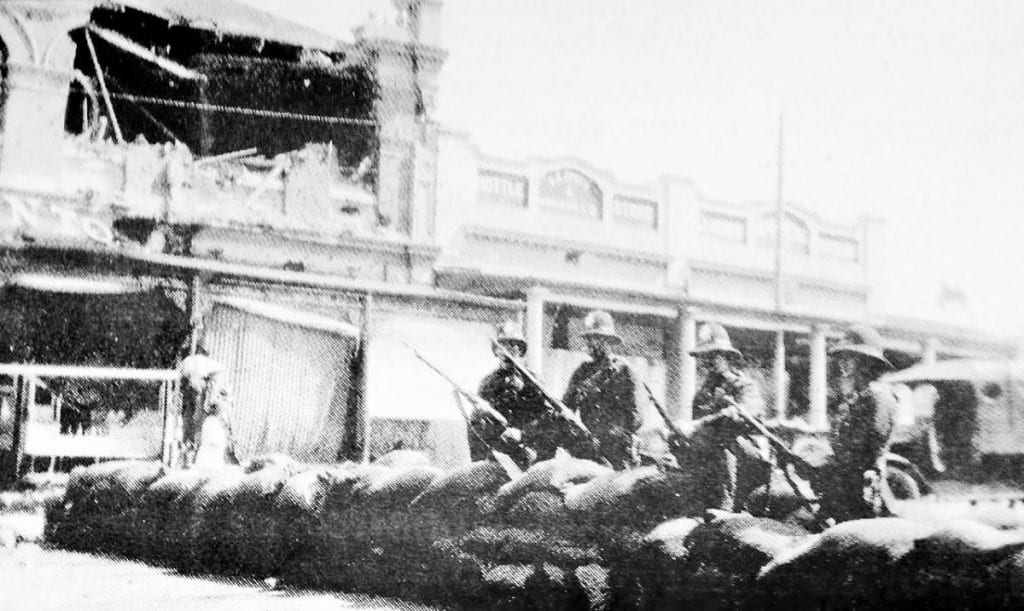

Smuts, too, was using air power to deadly effect, not only in policing ‘tribal peoples’.[17] In January 1922, white miners on the Rand went on strike against wage cuts. Within weeks, their action had garnered sufficient support to escalate into a general strike. Strike-breakers and police were subjected to violent counter-attack and for a moment it seemed as if the established order might give way. In March Smuts declared martial law, ordered in the army and bombarded the strikers from the air. As if to confirm his earlier views, aerial bombing was critical to the ending of the strike.[18] However, the whole affair cost him the 1924 general election.

Soldiers by a barricade in Johannesburg, 1922. Bomb damage is clearly visible in the background. www.theheritageportal.co.za

The paths of Smuts and Harris would cross again during the Second World War. Smuts, once again South African premier, joined Churchill’s war cabinet and was fulsome in his support of Harris as Commander in Chief of RAF Bomber Command.[19] Harris for his part praised Smuts as ‘one of the finest fellows who ever stepped this world’.[20] It was Harris who made the connection between Smuts’s early vision for the RAF and how the bombing war was executed from 1943:

‘Though Smuts had predicted how the air war would develop as long ago as 1917, I could see that he was astounded by what I showed him at Bomber Command; it was then that he realised in full for the first time what our bomber offensive meant to the war as a whole. I knew I was assured of his support in military affairs if I should require it.’ [21]

Heather Hughes

The Smuts Report has been transcribed from the copy in the possession of the RAF Museum, at https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/london/whats-going-on/news/read-the-smuts-report/ [last accessed 30 March 2018]

Note: the numbering in this transcription has kept as close as possible to the original; sub-sections, however, have been indicated by letters, rather than by Arabic numerals, as in the original.

Report by General Smuts on Air Organisation and the Direction of Aerial Operations – August, 1917

- Our first report dealt with the defence of the London area against air raids.

- We proceed to deal in this report with the second term of reference: the Air organisation generally and the Direction of Air Operations. For the considerations which will appear in the course of this report we consider the early settlement of this matter of vital importance to the successful prosecution of the war. The three most important questions which press for an early answer are :-

- Shall there be instituted a real Air Ministry responsible for all Air Organisation and operations.

- Shall there be constituted a unified Air Service embracing both the present R.N.A.S and R.F.C? And if this second question is answered in the affirmative, the third question arises :-

- How shall the relations of the new Air Service to the Navy and the Army be determined so that the functions at present discharged for them by the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C. respectively shall continue to be efficiently performed by the new Air Service?

- The subject of general air organisation has in the past formed the subject of acute controversies which are now, in consequence of the march of events, largely obsolete, and to which a brief reference is here made only in so far as they bear on some of the difficulties which we have to consider in this report. During the initial stages of Air development, and while the role to be performed by an Air service appeared likely to be merely ancillary to naval and military operations, claims were put forward and pressed with not small warmth, for separate Air services in connection with the two old-established war services. These claims eventuated in the establishment of the R.N.A.S and R.F.C., organised and operating on separate lines in connection with and under the aegis of the Navy and Army respectively, and provision for their necessary supplies and requirements was made separately by the War Office and Admiralty. The competition, friction and waste thus arising led to the institution of an Air Committee intended to preserve the peace and secure co-operation if possible. Its career was, however, cut short by an absence of all real power and authority and by political controversies which arose in consequence. It was followed by the present Air Board, which has a fairly well defined status and had done admirable work, especially in settling the type and patterns of engines and machines and in co-ordinating and controlling supplies to both the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C.

- The utility of the Air Board is, however, severely limited by its constitution and powers. It is not really a Board, but merely a confidence [conference]. Its membership consists almost entirely of representatives of the War Office, Admiralty and Ministry of Munitions, who consult with each other in respect of the claims of the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C. for their supplies. It has no technical personnel of its own to advise it, and it is dependent on the officers which the departments just mentioned place at its disposal for the performance of its duties. These officers, especially the Director General of Military Aeronautics, are also responsible for the training of the personnel of the R.F.C. service. Its scope is still further limited in that it has nothing to do either with the training of the personnel of the R.N.A.S. or with the supply of lighter-than-air craft, both of which the Admiralty has jealously retained as its special perquisites. Although it has a nominal authority to discuss questions of policy, it has no real power to do so, because it has not the independent technical personnel to advise it in that respect, and any discussion of policy would simply ventilate the views of its naval and military members. Under the present constitution and powers of the Air Board, the real directors of war policy are the Navy and Army, and to the Air Board is really allotted the minor role of fulfilling their requirements according to their ideas of war policy. Essentially the Air Service is as subordinated to military and naval direction and conceptions of policy as the artillery is, and, as long as that state of affairs lasts, it is useless for the Air Board to embark on a policy of its own, which it could neither originate nor execute under current conditions.

- The time is, however, rapidly approaching when that subordination of the Air Board and the Air Service could no longer be justified. Essentially the position of an Air Service is quite different from that of an Artillery Arm, to pursue our comparison: Artillery could never be used in war, except as a weapon in Naval or Military or air operations. It is a weapon, an instrument ancillary to a Service, but could not be an independent Service itself. The Air Service on the contrary can be used as an independent means of air operations. Nobody that witnessed the attack on London on 11th July could have any doubt on that point. Unlike Artillery, an air fleet can conduct extensive operations far from and independently of, both Army and Navy. As far as can at present for foreseen, there is absolutely no limit to the scale of its future independent war use. And the day may not be far off when aerial operations with their devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war, to which the older forms of military and naval operations may become secondary and subordinate. The subjection of the Air Board and Service could only be justified on the score of their infancy. But that is a disability which time can remove, and in this respect the march of events has been very rapid during the war. In our opinion there is no reason why the Air Board should any longer continue in its present form as practically no more than a Conference room between the older Services, and there is every reason why it should be raised to the status of an independent Ministry in control of its own War Service.

- The urgency for the change will appear from the following facts. Hitherto aircraft production has been insufficient to supply the demands of both Army and Navy, and the chief concern of the Air Board has been to satisfy the necessary requirements of those Services. But that phase is rapidly passing. The programme of aircraft production which the War Cabinet has sanctioned for the following 12 months is far in excess of Army and Navy requirements. Next Spring and Summer the position will be that the Army and Navy will have all the Air Service required in connection with their operations; and over and above that there will be a great surplus available for independent operations. Who is to look after and direct the activities of their available surplus? Neither the Army nor the Navy is specially competent to do so; and for that reason the creation of an Air Staff for planning and directing independent Air Operations will soon be pressing. More than that: the surplus of engines and machines now being built should have regard to the strategical purpose to which they are going to be put. And in settling in advance the types to be built, the operations for which they are intended apart from naval or military use should be clearly kept in view. This means that the Air Board has already reached the stage where the settlement of future war policy in the Air war has become necessary. Otherwise engines and machines useless for independent strategical operations may be built. The necessity for an Air Ministry and Air General Staff has therefore become urgent.

- The magnitude and significance of the transformation now in progress are not easily realised. It requires some imagination to realise that next Summer, while our Western front may still be moving forward at a snail’s pace in Belgium and France, the Air battle front will be far behind on the Rhine, and that its continuous and intense pressure against the chief industrial centres of the enemy as well as on his lines of communication may form the determining factor in bringing about peace. The enemy is no doubt making vast plans to deal with us in London if we do not succeed in beating him in the Air and carrying the war into the heart of his country. The questions of machines, aerodromes, routes and distances, as well as nature and scope of operations require careful thinking out in advance, and in proportion to our foresight and preparations will our success be in these new and far-reaching developments. Or take again the case of a subsidiary theatre: there is no reason why we may not gain such an overpowering air superiority in Palestine as to cut the enemy’s limited and precarious railway communications, prevent the massing of superior numbers against our advance, and finally to wrest victory and peace from him. But careful Staff work in advance is here in this terra incognita of the Air even more essential than in ordinary naval and military operations which follow a routine consecrated by the experience of centuries of warfare on the old lines. The progressive exhaustion of the man-power of the combatant nations will more and more determine the character of this war as one of arms and machinery rather than of men. And the side that commands industrial superiority and exploits its advantages in that regard to the utmost, ought in the long run to win. Man-power in its war use will more and more tend to become subsidiary and auxiliary to the full development and use of mechanical power. The submarine has already shown what startling developments are possible in naval warfare. But to secure the advantages of this new factor for our side, we much not only make unlimited use of mechanical genius and productive capacity of ourselves and our American allies. We must create the new directing organisation – the new Ministry and Air Staff which could properly handle this new instrument of offence, and equip it with the best brains at our disposal for the purpose. The task of planning the new Air Service organisation and thinking out and preparing for schemes of aerial operations next Summer must tax our experts and no time should be lost in setting the new Ministry and Staff going. Unless this is done, we shall not only lose the great advantages which the new form of warfare promises, but we shall end in chaos and confusion, as neither the Army nor Navy nor the Air Board in its present form could possibly cope with the vast developments involved in our new Aircraft programme. Hitherto the creation of an Air Ministry and Air Service has been looked upon as an idea to be kept in view but not realised during this war. Events have, however, moved so rapidly, our prospective aircraft production will soon be so great, and the possibilities of aerial warfare have grown so far beyond all previous expectations, that the change will brook no further delay and will have to be carried through as soon as all the necessary arrangements for the purpose can be made.

- There remains the question of the new Air Service and the absorption of the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C. into it. Should the Navy and Army retain their own special Air Services in addition to the Air Forces which will be controlled by the Air Ministry? This will make the confusion hopeless and render the solution of the Air problem impossible. The maintenance of three Air Services is out of the question, nor indeed does the War Office make any claim to a separate Air Service of its own. But as regards Air work, the Navy is in exactly the same position as the Army; the intimacy between aerial scouting or observation and naval operations is not greater than that between long range artillery work on land and aerial observations or spotting. If a separate Air Service is not necessary in the one case, neither it is necessary in the other. And the proper and indeed only possible arrangement is to establish one unified Air Service which will absorb both existing services under arrangements which will fully safeguard the efficiency and secure the closest intimacy between the Army and the Navy and the portions of the Air Service allotted or seconded to them.

- To secure efficiency and smooth working of the Air Service in connection with naval ad military operations, it is not only necessary that in the construction of aircraft and the training of the Air personnel the closest attention shall be given to the special requirements of the Navy and the Army. It is necessary also that all Air units detailed for naval or military work should be temporarily seconded to those services and come directly under the orders of the naval or army commanders of the forces with which they are associated. The effect of that will be that in actual working practically no change will be made in the Air work as it conducted today, and no friction could arise between the Navy or Army commands and the Air Service allotted to them. It is recognised, however, that for some years to come the Air Service will, for its efficiency, be largely dependent of the officers of the Navy and Army who are already in this work or who may in future elect to join it permanently or temporarily. The influence of the Regular officers of both services on the spirit, conduct and discipline of the present Air Forces has been and it is advisable that the Air Board should still be able to draw on the older services for the assistance of trained leaders and administrators. Further, it is equally necessary that a considerable number of officers of both Navy and Army should be attached for a part of their Service to the Air Service, in order that Naval and Military Commanders and Staff Officers may be trained in the arm and able to utilise to advantage the contingents of the Air Forces [that] will be put at their disposal. The organisation of the Air Force, therefore, should be such as to allow the seconding of officers of the Navy and Army for definite periods – not less than four or five years – to the Air Service. Such officers would naturally, after their first training, be chiefly employed with the Naval and Military contingents, in order to secure close co-operation in Air work with their own services. In similar fashion it would be desirable to arrange for the transfer of expert warrant and petty or non-commissioned officers from the Navy and Army to the new service.

- To summarise the above discussion we would make the following recommendations:

- That an Air Ministry be instituted as soon as possible, consisting of a Minister with a consultative Board on the lines of the Army Council or Admiralty Board, on which the several departmental activities of the military will be represented. The Ministry to control and administer all matters in connection with aerial warfare of all kinds whatsoever, including lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air craft.

- That under the Air Ministry and Air General Staff instituted on the lines of the Imperial General Staff responsible for the working out of war plans, the direction of operations, the collection of intelligence and training of the Air personnel; that this Staff be equipped with the best brains and practical experience available in our present Air Services, and by periodic appointment to the Staff of officers with great practical experience from the front due provision be made for the development of the Staff in response to the rapid advance of this new Service.

- That the Air Ministry and General Staff proceed to work out the arrangements necessary for the amalgamation of the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C. and the legal constitution and discipline of the new Air Service, and to prepare the necessary draft legislation and regulations, which could be passed and brought into operation next Autumn and Winter.

- That the arrangements referred to shall make provision for the automatic passing of the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C. personnel to the new Air Service by consent, with the option to those officers and other ranks who are merely seconded or lent of reverting to their former positions.

- There are legal questions involved in this transfer, and the rights of officers and men must be protected, but no dislocation need be anticipated.

- That the Air Service remain in intimate touch with the Army and Navy by the closest liaison or by direct representation of both on the Air General Staff, and that, if necessary, the arrangements for close so-operation between the three services be reviewed from time to time.

- That the Air General Staff shall from time to time attach to the Army and the Navy the Air units necessary for naval and military operations, and such units shall, during the period of such attachment, be subject for the purpose of operations, to the control of the respective naval and military command. Air units not so attached to the Navy and Army shall co-operate under the immediate direction of the Air General Staff.

- That provision be made for the seconding or loan of regular officers of the Navy and Army to the Air Service for definite periods, such officers to be employed, as far as possible with the naval and military contingents.

- That provision be made for the permanent transfer, by desire, of officers and other ranks from the Navy and Army to the Air Services.

- In conclusion we would point out how undesirable it would be to give too much publicity to the magnitude of our Air construction programme and the real significance of the changes in organisation now proposed. It is important for the winning of the war that we should not only secure Air predominance, but secure it on a very large scale; and having secured it in this war we should make every effort and sacrifice to maintain it for the future. Air supremacy may in the long run become as important a factor in the defence of the Empire as Sea supremacy. From both these points of view it is necessary that not too much publicity be given to our plans and intentions which will only have the effect of spurring our opponents to corresponding efforts. The necessary measures should be defended on the grounds of their inherent and obvious reasonableness and utility, and the desirability of preventing conflict and securing harmony between naval and military requirements.

[1] Richard Steyn, Jan Smuts: Unafraid of Greatness. Johannesburg and Cape Town, Jonathan Ball, 2015, p. 85.

[2] Sir David Henderson has been advanced as another worthy claimant: see https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/the-forgotten-father-of-the-royal-air-forc/ [accessed 30 March 2018]

[3] Bill Nasson, The South African War, 1899-1902. London, Arnold, 1999.

[4] Kenneth Ingham, The Conscience of a South African: Jan Christiaan Smuts. London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986; Mark Andrews, interview with Sir Arthur Harris, British Forces Broadcasting Services, 1977. Imperial War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80000925 [accessed 30 March 2018].

[5] For a detailed discussion of the campaign, see Ian van der Waag, ‘The battle of Sandfontein, 26 September 1914: South African military reform and the German South-West African campaign, 1914-1915’. First World War Studies 4, 2, 2013, 141-165.

[6] Malcom Cooper, ‘Blueprint for confusion: the administrative background to the formation of the Royal Air Force, 1912-1919’. Journal of Contemporary History 22, 3, 1987, pp. 437-453.

[7] Steyn, Jan Smuts, pp. 105-6.

[8] Tilman Dedering, ‘Air power in South Africa, 1914-1939’. Journal of Southern African Studies 41, 3, 2015, 451-465. The Aviation Corps developed into the South African Air Force under the leadership of Pierre van Reyneveld in 1920, making it the earliest of the independent dominion air services.

[9] For a detailed study of the organisational arrangements involved, see Cooper, ‘Blueprint for confusion’.

[10] James Corum, ‘The myth of air control: reassessing the history’. Aerospace Power Journal, Winter 2000, pp.61-77.

[11] V.G. Kiernan, European Empires from Conquest to Collapse, 1815-1960. London, Fontana, 1982, p. 195.

[12] David Omissi, Air Power and Colonial Control: The Royal Air Force 1919-1939. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1990.

[13] Cited in David Killingray, ‘“A swift agent of government”: air power in British colonial Africa, 1916-1939’. The Journal of African History 25, 4, 1984, p.429.

[14] Michael Collins, ‘A technocratic vision of empire: Lord Montagu and the origins of British air power’. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 45, 4, 2017, 652-671.

[15] Cited in Killingray, “A swift agent”, p. 441

[16] Cited in Nicolas Davies, Blood on our Hands: The American Invasion and Destruction of Iraq. Ann Arbor MI, Nimble Books, 2010, p. 227

[17] Smuts had ordered the deployment of aircraft to put down the so-called Bondelswartz Rebellion against the operation of a dog tax in South West Africa. See Richard Freislich, The Last Tribal War. A History of the Bondelswart Uprising. Cape Town, Striuk,1964. See also Andries Marius Fokkens, ‘The role and application of the Union Defence Force in the suppression of internal unrest, 1912-1945.’ M Military Science Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, 2006.

[18] Jeremy Krikler, The Rand Revolt: The 1922 Insurrection and Racial Killing in South Africa. Johannesburg and Cape Town, Jonathan Ball, 2005.

[19] Boog, H. G. Krebs and D. Vogel (eds) The Strategic Air War in Europe and the War in the West and East Asia 1943-1944/45. Volume VII of Germany and the Second World War, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2006, p. 84.

[20] Mark Andrews, interview with Sir Arthur Harris.

[21] Arthur Harris, Bomber Offensive. Barnsley, Pen and Sword, 2005 [1947], p. 151.