Editors’ note

Adalberto Di Corato researched the bombings of Turin as part of his MA in History. The official reports he quoted – here translated for the first time in English – may be of special interest for those who want to investigate of Bomber Command operations from the perspective of civilians. We welcome his contribution as guest blogger and wish him every success in his career.

The editorial team

Introduction

This blogpost summarises the dissertation “The War of Destruction. Military Strategy and the Role of Institutions: Turin as a Case Study” (supervisor Professor Marco Di Giovanni). It was produced in fulfilment of the MA in Historical Sciences I had attended at the University of Turin from 2016 to 2019. My research focused on the way Turin’s public institutions were involved in the air war from 1940 to 1945.

Bomb-damaged homes in Turin, circa 1943. Source: Wikimedia / Public domain

The first part of the research explored the preparedness measures implemented by the fascist regime during the 30s: adoption of gas masks, provisions of shelters, and arrangements for the defence of industries. The second part researched the way of public institutions (UNPA (1), antiaircraft defences, the Fascist Party, and the firefighters) responded to the unique challenges posed by the air war on Turin. This piece is an abridged version of the latter.

The Air War on Turin

The Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force started bombing Turin on 12th June 1940, immediately after Italy entered the war. Until late October 1942, Bomber Command carried out few small-scale operations, prioritising military targets while at the same time avoiding nearby areas. The RAF caused only a few casualties among civilians (36 deaths and 83 wounded), inflicting limited damage (2).

In a marked departure from the above, the British soon started a massive area bombing campaign on the city. It began in late October 1942 and culminated between July and August 1943. The area bombing doctrine was primary intended to target the whole city in order to cause as many casualties as possible, with the purpose of spurring the population to rebel against the regime. This phase resulted in 1,395 deaths and 1,582 wounded among the civilians, combined with widespread destruction (3).

Primary sources kept in local archives strongly support the view that local organisations (the UNPA, the Party, the antiaircraft defences, and the firefighters) were placed under enormous stress. This in mainly because the fascist regime, in the years leading to the war, ignored most of their requests for both funding and adequate equipment.

The main public institution tasked to train and protect civilians was the UNPA. Its pitiful state was eloquently captured by the following letter, now in the Turin State Archive, sent on 28th October 1941 by the Prefect of Turin:

I’m receiving many worrying complaints from depending units about clothes deficiencies, especially in regards of the early onset of intense wintry conditions. U.N.P.A. members are currently kitted out in simple canvas overalls, still waiting for the promised fabric uniforms from Rome. […] Even an extra allocation of blankets for the night is absolutely necessary, as repeatedly pointed out (4).

The overall precarious state of the UNPA and other institutions worsened once the British started their massive area bombing campaign on Turin in October 1942.

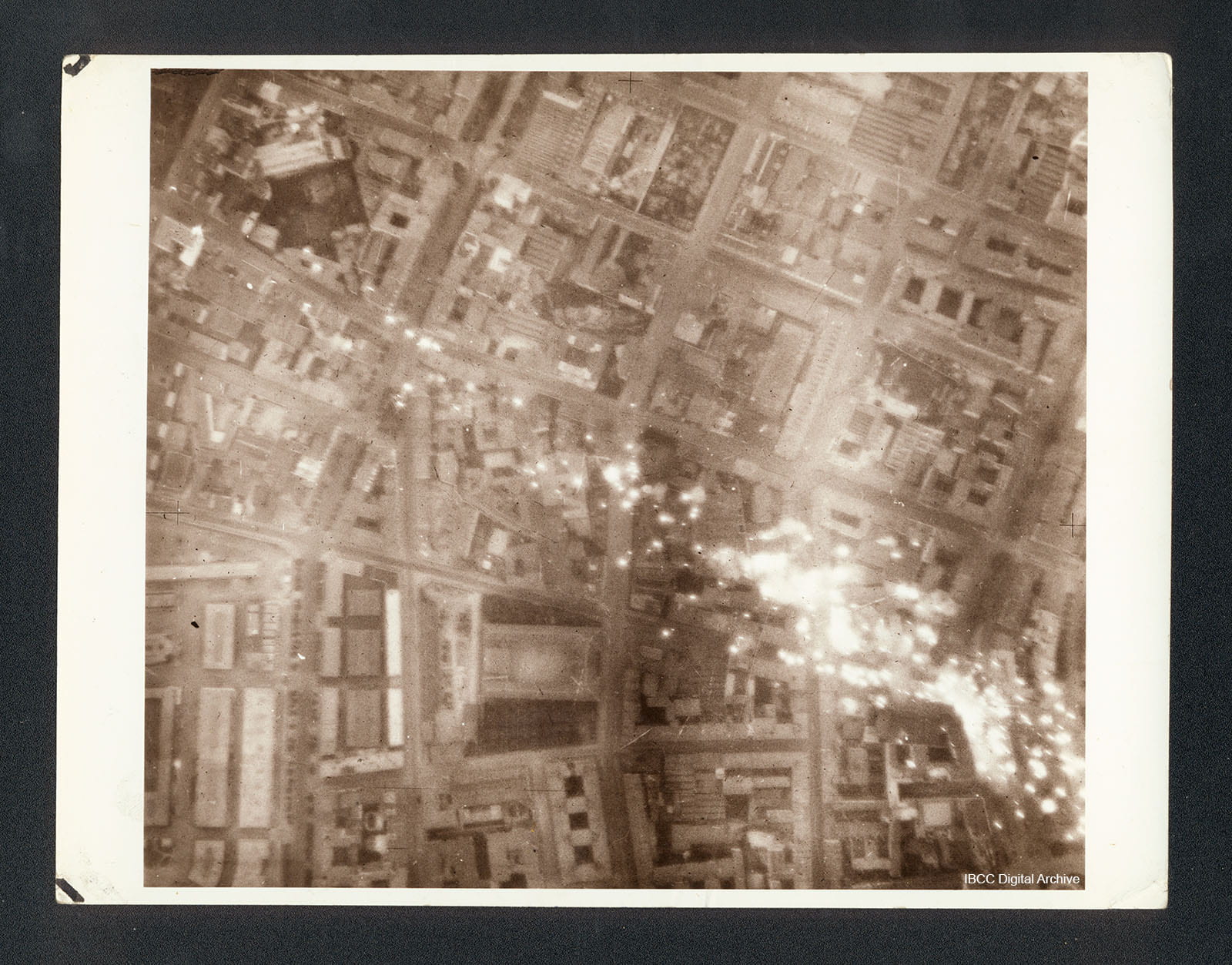

Turin, 9 Squadron, 18/19 November 1942 Commemorative picture of Lancaster for attack on Turin. In a circle at the top a Lancaster on the ground with engines running. Underneath a box with caption ‘Turin, 9 Squadron, 18/19 November 1942’. At the bottom a box with crew names ‘S/Ldr Clyde-Smith, Sgt Nancekivell, F/Sgt Webster, P/O Higginson, Flt Lt Skinner, Sgt Pleasance, Sgt Kearne’. Source: IBCC Digital Archive

After the heavy 20th November 1942 operation that caused 117 deaths and 120 wounded, the population started a spontaneous mass evacuation. More than 300.000 left the city (5). That caused a vivid impression on the Minister of Public Works Giuseppe Gorla, who visited Turin at that time: he compared it with the Biblical exodus of Hebrews (6).

Carlo Chevallard, a local entrepreneur, wrote in one of the most interesting Turin war diaries:

The most impressive aspect is the lack of leadership which became evident in the days following the two attacks: Fabbriguerra (7), Corporations (8), Prefecture, Trade Unions, Unpa, Gruppi Rionali (9) are all acting whimsically without an organic plan; orders and directives are often contradictory.

Chevallard noted lax discipline (in particular regarding traffic regulations and public transportation), but these trifling matters where not what he was most concerned about. It was rather

the outburst of hate for the Regime and the Duce: almost no one directs their anger to English who is waging war on us, but everybody is lashing out to whoever has dragged us into this predicament (10).

The documents in the historical section of Turin’s Firefighters Archive shed some light on the destruction caused by Bomber Command, and of the role played by the firefighters during the incident.

For example, 8th December 1942 operation (one of the most severe) is vividly described by the following report:

As per orders, we headed to Murazzi Po [a Turin district] with the firefighters. Upon arriving in Corso San Maurizio, house number 18, the enemy has already dropped incendiaries, and started bombing. Thus we decided to enter the shelter at 18 Corso San Maurizio. We have been inside for a few minutes when a bomb hit the left wing of the same house making it collapse. We tried to calm down the people who were inside. After tearing down a wall we came out via another passage leading to the garden. Meanwhile, incendiary bombs fell on the garage of the newspaper “La Stampa” situated at 20 Corso San Maurizio, where a substantial amount of flammable liquids were kept in the warehouse. By means of a car made available by “La Stampa” I sent immediately the firefighters Rolfo and Bobbio to headquarter, asking them to bring all the necessary to have at least a fire hose in place. Meanwhile, work started to contain the spread of the fire, which was getting out of control. This was helped by the garage caretaker and by some keen residents of the block of flats at 18. After almost four hours of hard work, we were able to contain the fire by using the hose, saving the flammable content of the warehouse and a part of the garage. All the men worked with zeal and eagerness, to the acclaim of bystanders (11).

Sometimes firefighters had to work continuously for hours. During the 13th July 1943 raid, which caused 792 deaths and 914 wounded, a report indicates that two squads have been dealing with an incident which lasted three days (12). The squads were relived every six hours, in turns:

The clearing of debris was started by the men and progressed faster with the help of the soldiers of the 1st Engineers Regiment. It proceeded without interruption until 7 PM of the day 16th July 1943-XXI (13). The rather dangerous job was accomplished with caution, factoring in all possible eventualities: all adequate measures were implemented, also securing unstable parts by improvised means. For instance, after having opened a breach in a corner of the shelter which was sealed off [by debris], we managed to extricate an unharmed soldier, who was accompanied to the hospital by some bystanders. Later, after having received instructions by the ‘capo fabbricato’ (14) about a spot where were three casualties were buried, these were taken out and identified as Bergasiani Bernardino son of Isacco, aged 18, Castagneri son of Giov. Battista, aged 58, Droetti Caterina daughter of Michele, aged 39 (15).

The bombings did not stop after the armistice of 8th September 1943. On the 8th November 1943, USAAF bombers attacked Turin en masse. Unlike the RAF, the USAAF zeroed in on specific targets such as the factories supporting Germany’s war effort and marshalling yards. Nevertheless, this bombing doctrine did not spare the civilians as the targets were near densely-populated districts and bombing was far from being accurate. One firefighters’ report describes the response after bombs hit a factory:

The “Squadra Celere” (16) was dispatched to the Microtecnica factory to put out a fire caused by incendiary bombs. Upon arriving at the scene, our work was not needed anymore, because the factory firefighters had done the job. Meanwhile, one employee pointed out that some people were buried under debris at 80 Via Pietro Giuria. We dashed to the place. As per report, the building was hit by a high-capacity bomb and collapsed. Some well-meaning people sprung to action and extricated a woman: Loro Angela, aged 67. A voice begging for help was heard among the broken beams and the rubble. We set about to the rescue and were soon able to establish a contact with the victim. Meanwhile, I required the assistance of the rubble-clearing squad, which after hours of work was able to rescue the casualty: Cattaneo Marino, aged 26. They then extracted two bodies, Loro Paolo, aged 63 and Beolotto Maria, the caretaker, who lived there. Other corpses still lie under the debris – clearing continues (17).

The results bear out the widespread lack of preparedness. All local institutions had to deal with an extremely difficult situation while poorly equipped and overstretched – despite that, as substantiated by reports, they worked above and beyond the call of duty. Their success is a testament to their abnegation and the spontaneous solidarity of civilians. Interestingly, the bombing did succeed in creating panic and the population openly voiced its disdain for the regime. The widespread dissatisfaction did not reach the intensity of an open revolt: the toppling of the fascist regime failed to materialise, contrary to the expectations of Allied planners. It is possible that the abnegation of responders, especially the firefighters, produced the feeling that damage can at least be contained, and a semblance of normality preserved. More research is needed to substantiate this hypothesis.

Adalberto Di Corato

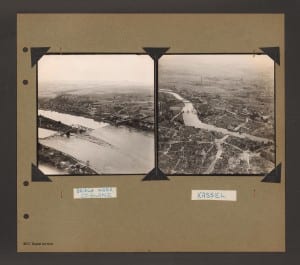

Appendix. David Donaldson reminisces an operation on Turin

It was one of those clear moon-light nights and the stars seem stand out in the sky; you feel you can put out your hand and grab one. As we flew on toward the Alps we could make out some of the little mountain villages against the background of snow. You could see their lights twinkling in the trees. The aircraft was going wonderfully well and we cleared the highest mountains by 3 or 4000 feet. You could see the ridges and peaks well defined and the moon shining on the snow. Flying over this sort of scenery was something completely new to us and pretty awe-inspiring because the nearest we had got to it was on the Munich raid when we’d seen the Bavarian Alps in the distance. The navigator came up and pointed out Mont Blanc away on our port side, he was able to identify it from its shape because he had actually climbed it. He was telling us how he was beaten by the weather when he had got to within 600 feet of the summit. Immediately we got to the other side of the Alps with no snow about it seemed by comparison intensely dark for a bit, it was like coming out of a lightened room into the blackout. Soon after that we started to glide down, loosing height very gradually and arrived slightly west of Turin. Other planes were already over the target because you could see their flares and there was a barrage of anti-aircraft fire in the sky. Our target was the Fiat works, and the whole time we were looking for them we were still gliding down to our bombing height. Actually we picked the works up in the light of somebody else’s flare. They were unmistakable. I’d never had such a target before. There seemed to be acres of factory buildings. We almost wept afterwards because we hadn’t got any more bombs to give them. Having located our target, we flew four or five miles away, turned round and made our run up over it. The wireless operator came along and stood beside me to have a look at the bombing, otherwise he wouldn’t have seen anything from his usual position. When he saw the light flak coming up from the works he said ‘Gosh, look at the Roman candles’. We made two attacks. As we came round afterwards to have a look, the fires which we’d started were going strong. There was a big orange-coloured fire burning fiercely inside one block of buildings. Having finished the job, we climbed to get enough height to cross the Alps again. Altogether we were over or round about the town for three quarters of an hour, and, whilst we were circling to gain height we saw somebody hit the Royal Arsenal good and proper.

The passage “We almost wept afterwards because we hadn’t got any more bombs to give them”, has a rational justification. Bombers en route to Italian cities had a reduced bombload to allow for a longer flight time, hence the disappointment. Source: IBCC Digital Archive

Notes

1) Unione Nazionale Protezione Antiaerea (National Anti Aircraft Protection Union)

2) ASCT, Archivio fotografico- Ufficio Protezione Antiaerea, 1945_9F02-06 e 2031_9F02-08.

3) ASCT, Archivio fotografico- Ufficio Protezione Antiaerea, 1945_9F02-06 e 2031_9F02-08.

4) ASTO, Prefettura, Gabinetto, I Versamento, m. 513.

5) Marco Gioannini, Giulio Massobrio, Bombardate l’Italia. Storia della guerra di distruzione aerea 1940 – 1945, Rizzoli, Milano 2007, p. 383.

6) Giuseppe Gorla, L’Italia nella II guerra mondiale. Diario di un milanese, ministro del Re nel governo di Mussolini, Badini & Castoldi, Milano 1959, p. 377.

7) Ministry of War Production

8) State agencies coordinating different industries.

9) Local city sections of the Fascist Party

10) Carlo Chevallard, Torino in guerra tra cronaca e memoria. Diario di Carlo Chevallard 1942 – 1945, Ed. Archivio Storico della Città di Torino, Torino 1995, p. 27.

11) ASVFF, relazione incendi 1942.

12) ASCT, Archivio fotografico- Ufficio Protezione Antiaerea, 1945_9F02-06 e 2031_9F02-08.

13) XXI = 21st Year of the Fascist Era, an indication that in every public and even private document had to be added to the ordinary Christian calendar date.

14) The “Capofabbricato” was a minor Fascist party official, tasked to enforce civil defence preparedness discipline within a block of flats.

15) ASVFF, relazione incendi 1943.

16) Rapid response team

17) ASVFF, relazione incendi 1943.

Abbreviations

ACS – Archivio Centrale dello Stato (Central State Archive) – Rome

ASTO – Archivio di Stato di Torino (Turin State Archive)

ASCT – Archivio Storico della Città di Torino (Turin Historical City Archive)

ASVFF – Archivio Storico dei Vigili del Fuoco (Firefighters’ Historical Archive)

Further reading

Emanuele Artom, Diari: gennaio 1940-febbraio 1944, Centro di documentazione ebraica contemporanea, Milano 1966.

Pier Luigi Bassignana, Torino sotto le bombe nei rapporti inediti dell’aviazione alleata, Edizioni del Capricorno, Torino 2012.

Pier Luigi Bassignana, Torino in guerra: la vita quotidiana dei torinesi ai tempi delle bombe, Edizioni del Capricorno, Torino 2013.

Paolo Bevilacqua, [et al.], I rifugi antiaerei di Torino, Paolo Emilio Persiari, Bologna 2018.

Carlo Chevallard, Torino in guerra tra cronaca e memoria. Diario di Carlo Chevallard 1942 – 1945, Ed. Archivio Storico della Città di Torino, Torino 1995.

Marco Gioannini, Giulio Massobrio, Bombardate l’Italia. Storia della guerra di distruzione aerea 1940 – 1945, Rizzoli, Milano 2007.

Giuseppe Gorla, L’Italia nella II guerra mondiale. Diario di un milanese, ministro del Re nel governo di Mussolini, Badini & Castoldi, Milano 1959.

Nicola Labanca (ed.), I Bombardamenti aerei sull’Italia, Il Mulino, Bologna 2012.