Laura Morelli is a contemporary artist who started her journey building relational machines: from deconstructing electronic toys for children to applying robotic technology. Since 2003 she has taken a keen interest in social issues working with people whom she shares the creative process with. In 2006, Laura founded and became president of the cultural association Di +, a charity whose core mission is promoting and delivering relational artistic projects.Laura has been officially invited to visit the IBCC Digital Archive on 5 September 2018, to addend its official launch. The interview was conducted by Alessandro Pesaro.

Laura, when your interest in aerial warfare started?

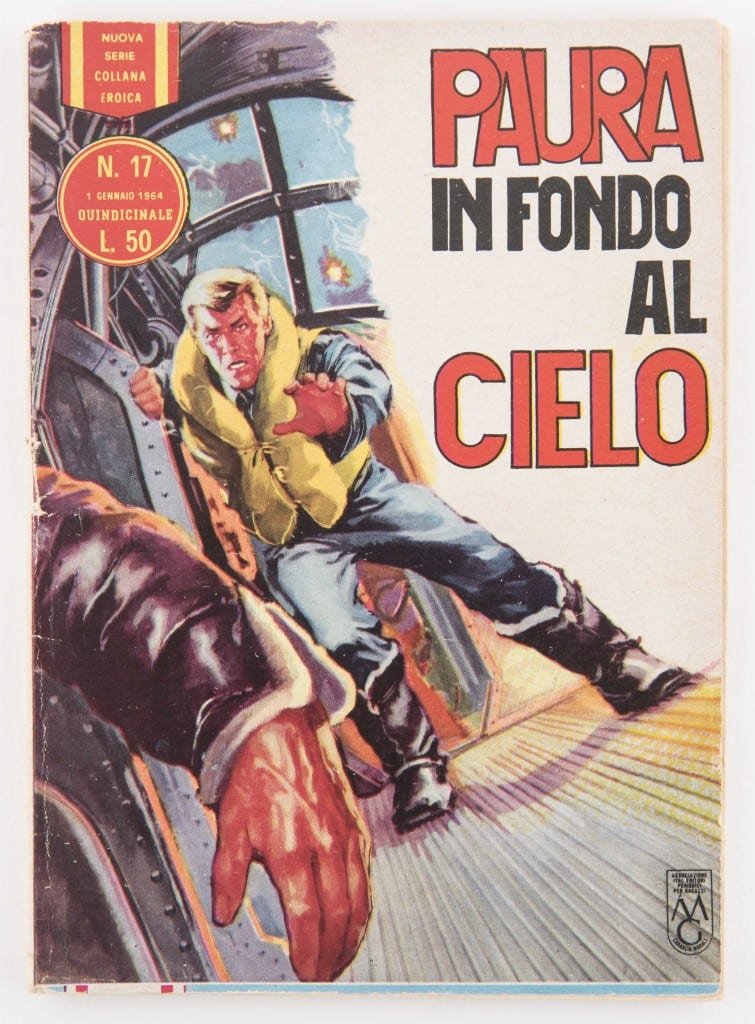

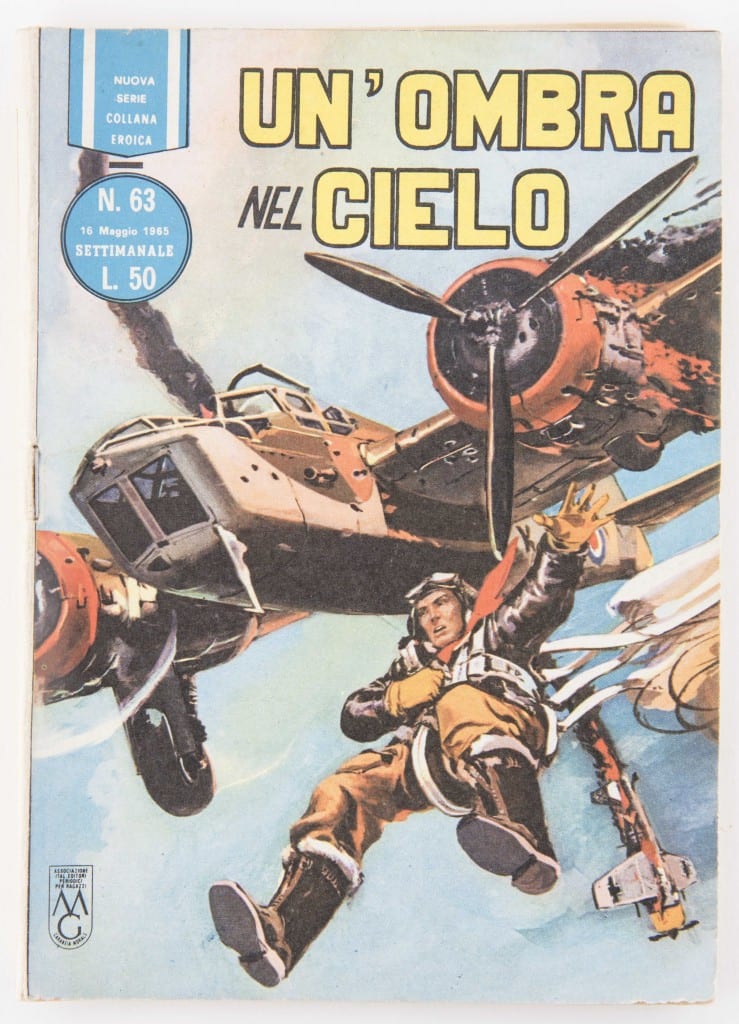

In 2005 I was shown a photograph taken inside a shelter in Dalmine, a little town in the Bergamo area. That image set something in motion and I soon discovered a host of stories of people who found themselves at the receiving end of the bombing war in Italy. I was instantly fascinated by the memories of bombing survivors in my family and determined to turn them into an art project. Thus “Bunker” was born in 2006.

Was it a one-off experience?

Quite the opposite. Bunker is part of a lifelong interest in some interconnected topics, namely human destructivity, violence, how people cope with suffering and grief, and the transformative power of art. My interest in social exclusion and silenced voices did the rest.

Is there a gender issue in the memorialisation of the bombing war?

Absolutely. While researching the bombing war in the Bergamo area I became aware of an obvious male / female inbalance: the predominant narrative is about male experiences narrated by male voices. Needless to say, women were those who bore the brunt of the war. The impact on their lives was multifarious because they found themselves in different roles: mothers, wives, widows, sisters, housemakers and caregivers. Despite the length and intensity of their suffering, their grieving process remains largely unrecognised.

How did you address this issue?

Contemporary art is all about suggesting new way of thinking, challenge preconceptions, force reflection, disrupt certainties, and explore the contradictions of the contemporary wold. On the other hand, crocheting is a time-honoured traditional craft, imbued with nurturing and protective connotations. Babies’ clothing is traditionally crocheted at home, thus resonating with motherhood, family, new life, and future. On top of that, this is a craft most women are already familiar with, hence regarded as natural and non-intimidating. Here my relational approach to art came into play: working with someone rather than for someone. So, why not crocheting a bomb?

Firstly, we carefully researched Allies’ weaponry. Size and shape of the bombs match those of the actual devices dropped on Italian targets but this was the only constrain: all patterns and textures have been devised by the women involved in the project, who have chosen colours and decorative motifs according to their own taste. Some women started from paper patterns, others used polystyrene templates. The craft is practiced according with the woman’s preferences, someone alone, others else in small groups, by women chit-chatting or simply enjoying each other presence. The rhythm of crocheting is slow as to suggest a thoughtful, healing experience even when the ‘offensive shape’ of a bomb was taking place. Lastly, fibres were impregnated with a synthetic resin strong enough to preserve the shape of the bombs without obscuring their delicate needlework texture. Once the resin has set, the bombs become free-standing structures which can be put on a pedestal or hanged.

A crochet bomb is a subtle visual play and gender allusions are transparent: by using a quintessentially feminine craft, women give shape to an object which has an obvious masculine overtone. Creation and destruction are inextricably intertwined. The delicate, fragile, almost ethereal substance of the bomb contrasts with its heavy metallic substance and ominous shape, the latter universally understood as a symbol of death, suffering and destruction. The result was stunning and the artworks resemble more hot air balloons than bombs. Lightweight and colourful, they suggest playfulness; on the other hand, they can almost be carried away by the same air through which real bombs hissed down in wartime. In this sense, they have a poetic quality.

What about the women who were involved in the project?

Women came on board for different reasons: some were at the receiving end of the bombing war, others have family ties with survivors, others were keen to explore new ways to reconnect with their past, like the group of nuns belonging to the same religious order which gave shelter to those who were orphaned as consequence of the raids. What struck me most is the fact that all the 70 women who partook in the project showed up at different official openings and took a tremendous sense of pride in their work. People in the 50 to 70 age group do not seem to be the standard patronage of contemporary art exhibitions, but their response was overwhelming and the sense of community palpable.

Where are the crochet bombs now?

After the end of the 2006-2007 delivery phase, some bombs were bought by collectors, other toured various locations, one is on permanent display inside the “Bunker Breda” a network of underground shelters now used as educational facility. In 2016 a group was on temporary display at the Milan Catholic University: bombs were hung inside the university chapel, suspended along the nave as to suggest a descending line toward the altar. Putting the bombs on display inside a Catholic church amplified the message of the installation and added a new dimension to it, especially at a juncture when catholic priests were killed by terrorists.

Bombs are currently on the display at the “CONTEXTO” collective art exhibition (Edolo, 14 July – 9 September).

A final thought, please…

Silence is rooted in many reasons: art can find the right words to say it.

Alessandro Pesaro, Digital Archive Developer